Durham Castle is a testament to the enduring influence of the medieval Prince-Bishops, whose legacy can still be felt in the fabric of the building and the wider landscape of the Palatinate. It is a rare example of a medieval fortress that has adapted and evolved over the centuries, while still preserving its essential character.

From Keith Johnston’s ‘The Castles of England, Scotland and Wales’

For this week's Meander, I was back in Durham, and this time, I went to the castle. While I mentioned it in passing in an earlier Meander, I haven't had much chance to explore it, given that it's part of Durham University and a 'working building', which is usually closed to visitors.

The castle is, at its core, a Norman fortress cum palace that sits close to the magnificent Durham Cathedral. The two are iconic landmarks of northeast England and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I think one of the best views of the pair is from near Durham’s railway station. It’s where I took the photograph above of the striking architectural ensemble perched high on a rocky promontory, almost surrounded by the River Wear.

Upon ascending to the English throne in 1066, William the Conqueror quickly realised the need to secure his kingdom against potential Scottish incursions. He recognised that ensuring the Earldom of Northumbria (essentially what we now call northeast England) was under his control was essential for safeguarding the north of his realm. However, he also understood that Northumbria's distance and its people's independent nature made it challenging for a king in southern England to govern it effectively.

Since Æthelfrith, Northumbria's first King, and even after England's ‘creation’ under King Athelstan, Northumbria remained largely independent from the rest of England for around four hundred years. At the time of the conquest, Northumbria's two most powerful men were the Earl of Northumbria, Morcar and the Bishop of Durham, Æthelwine. The Bishops of Durham traditionally held considerable influence, being the successors to the earlier Bishops of Lindisfarne, who had included highly respected Northumbrians such as St. Cuthbert. By confirming the powers and privileges of Morcar and Æthelwine, William aimed to secure the loyalty of the two parties and thereby ensure sufficient protection of northern England from potential threats by the Scots.

Alas, for William, it was not to be, and the pair rebelled against him, so William decided to install Robert Comine, a Norman noble, as the Earl of Northumbria. However, Northumbrian forces massacred Comine and his seven hundred men in Durham before he had the opportunity to assume his office. In revenge, William led his army in a bloody and devastating raid into Northumbria, imprisoning the earl and bishop, and it was in that confinement that they both died.

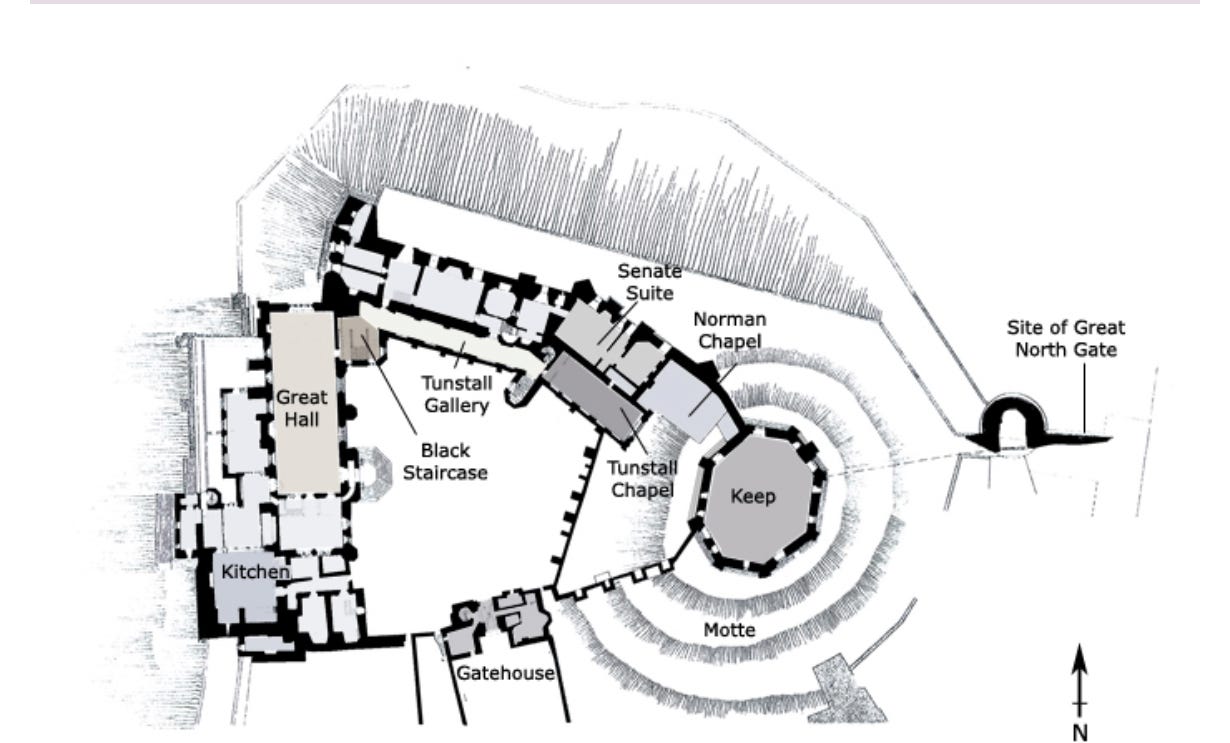

King William then appointed William Walcher, a Norman, as the new bishop, and a loyal (so William thought) Anglo-Saxon, Waltheof, from the old Earl of Northumbria's line, as the new earl. It was Waltheof who built the first castle at Durham as a residence for Walcher. Like many early Norman motte-and-bailey castles, it replaced an Anglo-Saxon structure that stood in a perfect defensive location high on a peninsula, surrounded by the River Wear on three sides.

But surprise, surprise, Waltheof then rebelled. Unsuccessfully, as it turned out and after his execution, William appointed Walcher as earl and bishop. Wishing to establish Durham Castle as a symbol of his spiritual and temporal power, Walcher oversaw its expansion. While historical sources mention that the castle’s keep was still of wood, Walcher built the newer buildings of stone.

Fatally for Walcher, the people of Northumbria remained resistant to Norman control, and yet another violent anti-Norman uprising led to the murder of Walcher.

Despite this, after King William's death, his son, William Rufus, decided to continue his father's policy towards Northumbria, combining the powers of earl and bishop under Bishop William St. Carileph, Walcher's successor. However, Carileph’s authority extended only to the area of Northumbria south of the Rivers Tyne and Derwent. This area became known as the 'County Palatine of Durham' (essentially County Durham today) or the Bishopric of Durham.

The Palatine was virtually a separate state, serving as a defensive ‘buffer zone’ sandwiched between England and the often-treacherous Northumbrian-Scottish borderland. Carileph and successive bishops had nearly all the powers within their Palatine that the king had in the rest of England. For this reason, history has named these bishops of Durham the 'Prince Bishops'. Their powers enabled them to hold their own parliament, administer their own laws, mint their own coins, raise their own armies, appoint their own sheriffs and Justices, collect revenue from coal mines, and levy their own taxes and customs duties. They could also create fairs and markets, issue charters, administer the forests, and salvage shipwrecks. Indeed, the Prince Bishops lived like kings in their castle, also known as their 'palace', in Durham.

Such a powerful position as Durham's Prince Bishop, arguably the most important non-royal in England, proved attractive, and a remarkable chap who attained it was Ranulf Flambard. The son of a Norman cleric, Flambard (meaning "incendiary" or "torchbearer," possibly referring to his fiery personality), followed in his father's footsteps into the Church and helped establish the Domesday Book. When William Rufus succeeded his father to the throne, Flambard was chaplain to Maurice, Bishop of London, and keeper of the royal seal (more or less Lord Chancellor). In the years that followed, Flambard proved he had an eye for business, and Rufus appointed him chief treasurer. However, it was in 1099 that Flambard secured his most significant promotion and was enthroned as a prince bishop. It was under his leadership that the construction of Durham's cathedral began; however, Flambard also soon gained a reputation for corruption.

Flambard had been prince bishop for less than a year when William Rufus died, most likely murdered while riding in the New Forest. The new King Henry I, noting Flambard's dubious reputation, stripped him of his office, and he became the newly built Tower of London's first prisoner.

Imprisonment for important personages was quite different then, and Flambard’s 'lodging' was comfortable. Henry also granted permission for Flambard to utilise his financial resources to support his staff, who delivered meals from outside the Tower. Privileges extended for him to hold banquets, and he shrewdly invited his gaolers to these, slowly earning their trust. At a banquet on 2 February 1101, Flambard arranged for the serving of substantial quantities of alcohol. After his captors became intoxicated, Flambard used a rope smuggled into his cell to descend the Tower walls. However, the rope wasn't quite long enough. Yet, despite injuring himself after falling some 20 feet, he still managed to scale the outer wall where his allies had left him a horse. Riding it away from London, he eventually met up with a ship moored downriver that took him to Normandy and sanctuary with Henry I's elder brother, Robert Curthose, with whom he soon set about helping in his plans to invade England.

However, the royal brothers reconciled, with Henry eventually restoring Flambard to his position as prince-bishop, which he maintained until his death. He oversaw the completion of Durham Cathedral, arguably the largest cathedral in northern Europe at the time, and fortified Durham Castle by building masonry walls around the peninsula on which the castle and cathedral are situated.

These walls, strengthened with flanking towers and buttress turrets, followed the hill's contours as they rose from the riverbank on all sides, except to the north, where the vulnerable neck of the Durham Peninsula lay. A forty-five-foot wall was built here, with a dry moat outside. A massive gate, the North Gate, allowed entry through the wall. Two other gates, Kings Gate and Water (or Bailey) Gate, which led to fords across the river, also permitted entry.

Acknowledging the strategic significance of the North Gate in the castle's defence resulted in enhancements, over the centuries, rendering it increasingly formidable. The gate's re-fortification in the early 15th century was the last significant defensive addition to the Castle. The gatehouse also served as the county jail until 1820, when the Bishop of Durham allocated funds for the construction of a new prison. Demolishment of the gate followed, as there was no longer a need for such a defence, and it was also an obstruction to traffic. Despite its once importance, there is little sign of its existence today.

Moving on nearly two hundred years from Flambard, we come across another interesting character, Anthony Bek, a warrior knight, politician, and bishop who began to transform the austere castle into a fortified residential palace with the addition of comfortable private apartments on the upper floors of the castle's Keep, adorned with lavish decorations and furnishings. In contrast, the servants' quarters were in the basement, with minimal natural light and ventilation. The kitchens were also located there, providing warmth for the rest of the Keep during cold winters.

Anthony Bek was born into a family of Lincolnshire knights. After attending Oxford University, he joined the clergy, coming to the attention of Prince Edward, the heir to King Henry III. As part of Edward's entourage, Bek rapidly rose through the ranks of the Church and accompanied the Prince when he went on a crusade in 1270. Bek became Prince Bishop of Durham in 1283 and joined Edward I's campaigns against the Scots (that earned Edward the sobriquet, ‘The Hammer of the Scots’, leading troops during the Wars of Scottish Independence. Pope Clement V appointed Bek ‘Patriarch of Jerusalem’ in 1307. However, it was only symbolic, as the ‘Holy Land’ was under Muslim control at the time.

One of the most elaborate tombs in Durham Cathedral is that of another long-serving Prince Bishop, Thomas Hatfield. Appointed at thirty-five years old, he held the position for thirty-six years until his death. Hatfield's extended tenure as bishop allowed him to have a significant influence on his diocese, and Hatfield College at Durham University now bears his name. Interestingly, however, given the prince bishop's role in keeping the Scots at bay, Hatfield was not in England when the famous Battle of Neville’s Cross took place. He was still on a military campaign, however.

Hatfield was with King Edward III, waging war in France. Following the resounding victory over the French at Crecy in 1346 by the English, the French King Philip invoked the terms of the 'Auld Alliance'. He asked his ally, King David II of Scotland, to retaliate for the defeat at Crecy by invading England. After rampaging their way through Northumbria for a few weeks, the 12,000-strong Scottish army led by David arrived outside the gates of Durham in October 1346, blissfully unaware that an English force comprising some 7,000 men raised from the northern counties of England had been quickly mobilised by the Archbishop of York. Due to the superior positioning of the English forces, the invaders faced significant disadvantages, causing their formations to disintegrate as they attempted to advance. Sensing defeat, many Scottish nobles fled the field, abandoning King David and his bodyguard to face the English alone. He was quickly captured and imprisoned, and in the year that followed, the English drove home their advantage and occupied virtually all southern Scotland.

It was Hatfield who replaced the castle's original Norman Keep with a strong defensive structure with nine-foot-thick walls to protect against invaders. Its octagonal shape was an improvement on earlier Keeps, which were square or rectangular. The advantage of an octagon is that it is much easier to defend as there are no 'blind spots', which was often a problem with square Keeps. The new Keep was as much a symbol of power as it was a utilitarian feature of a castle. However, with time, as the Bishop of Durham's residence evolved from a fortress into a palace, the Keep's defensive importance declined. The Keep then fell into disrepair until Durham University took over the Castle and rebuilt it. Today, it serves as student accommodation.

Moving forward approximately two hundred years, we encounter Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, one of the most important, respected, and controversial figures in Tudor England. He served as Prince Bishop of Durham for 29 years, during a period of political scandal and religious turmoil that saw significant changes in England. Tunstall built a reputation for his intellect from an early age, attending the universities of Oxford and Cambridge before studying law at Padua in Italy and entering the Church when he returned to England, rising through the ranks as a contemporary of the likes of Sir Thomas Moore. In 1530, Cuthbert succeeded Cardinal Wolsey as Bishop of Durham. Yet, given the times he played a dangerous game on the question of King Henry's divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, acting as one of Queen Catherine's counsellors. Unlike Bishop John Fisher and Sir Thomas More, however, Tunstall adopted a policy of passive obedience and acquiescence during the troubled years following the English Reformation. While Tunstall adhered firmly to Roman Catholic doctrine and practices, he accepted Henry as head of the Church of England. After some hesitation, Tunstall publicly defended this position, despite the schism with the Roman Catholic Church.

However, when Elizabeth I ascended to the throne, Tunstall refused to take the Oath of Supremacy and would not participate in the consecration of the Anglican Matthew Parker as Archbishop of Canterbury. Elizabeth removed Tunstall from office, had him arrested and held him in custody at Lambeth Palace. He died there a few weeks later, aged eighty-five, one of eleven Roman Catholic bishops to die in custody during Elizabeth's reign. We must thank Bishop Tunstall for expanding the Great Hall, a grand dining space that was created in the 14th century, featuring a minstrels' gallery and a magnificent hammer-beam roof. This was the heart of the castle, once the setting for lavish banquets and significant ceremonies. More soberly, it was used as a courtroom for legal proceedings. These days it's the student refectory, not a bad place to eat your cornflakes in the morning!

By the 18th century, the power of the prince bishops had been gradually eroding as the English monarchy became stronger and more centralised. Parliament grew in authority, especially after the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution, and the special privileges of the prince bishops began to look increasingly outdated and undemocratic. The final blow came with the Durham (County Palatine) Act of 1836, passed by Parliament that stripped the Bishop of Durham of his secular powers and transferred all judicial and political authority to the Crown and Parliament, making Durham, after nearly 800 years of semi-independent rule as virtually a kingdom within a kingdom, like any other English county. The age of the warrior-bishop ruling from a fortress was finally over. The Bishop of Durham continued to serve as a senior figure in the Church of England, albeit in a purely religious capacity.

The founding of the University of Durham occurred four years earlier, under the last Prince-Bishop, William van Mildert. After his death, Durham became an ordinary county, and the castle was handed over to the University, which became known as University College, the oldest of the Durham colleges. It remains a living, working building, with students residing and studying within its historic walls.

Durham Castle today is a blend of changing architectural styles, but despite nearly a thousand years of evolution, its Norman features, such as thick walls and rounded arches made of local sandstone, are still clearly visible. The castle's Norman Chapel is one of the oldest surviving chapels in England, with its original Romanesque architecture. The other chapel in the castle, named after its builder, is Tunstall's Chapel, featuring a stunning stained-glass window. On my visit, the University choir were practising in the chapel, and if I closed my eyes, I seemed transported back some five hundred years.

Another highlight of the castle is the Black Staircase, which is almost sixty feet high, deriving its name from the dark oak wood used in its construction.

As with any castle worth its salt, there are myths and legends surrounding it, and yes, there's a ghost, the so-called grey lady. Some say she was a tragic figure, possibly linked to a noble family or the Bishop's household. There have been numerous student reports of sightings of her walking silently up or down a staircase over the years, and tales of flickering lights and eerie cold spots abound. There is also supposedly a secret tunnel linking the castle to Durham Cathedral, similar to the Passetto di Borgo, which connects Vatican City to Castel Sant'Angelo, used by popes as an escape route in times of danger. The Durham Castle tunnel has long been the subject of local lore. However, no one has yet been able to prove its existence.

Today, Durham Castle is a blend of history and academic life. It is not just a thousand-year-old monument or ruin but an imposing and eye-catching home in which students live, dine, and study. It's a rare example of a Norman castle that remains inhabited and in regular use. Visiting it offers a glimpse into both its historic past and vibrant present. It is a place where centuries fall away, and ancient medieval stone echoes to the voices of the young and vibrant laughter of the present.

.

Thank you for another fascinating read, Harry.

A fascinating account. The hunger for power and intrigue still go on today.

It’s amazing how quickly the Normans exercised their power across England.