They [The Pitmen Painters] recorded their lives with such honesty, painting the ordinary, the mundane, the everyday and put it all down on paper, on canvas, on hardboard. They showed me that ordinary people's lives could be important and could be seen as art.

Mik Critchlow

Several of my Meanders have featured social documentary photographers such as Tish Murtha, Chris Killip, Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, and John Bulmer who worked in northeast England from the early 1960s, Their photographs are often featured in exhibitions; however, this week, I write after visiting a recently opened exhibition at the Whithorn Mining Museum that highlights someone I have only made passing reference to so far: Mik Critchlow, a photographer who also played a vital role in capturing the cultural identity of northeast England.

The region's traditional coal mining, shipbuilding, steelworks, railways and fishing industries shaped the area’s economy, architecture, culture, and social rhythm. This world of hard labour, both in its rise and fall, often caught the photographer’s eye.

What that 'attraction' brings with it is the contentious subject of ‘Poverty Porn’ especially as those industries declined and the resultant hardships to communities sometimes photographed in a depersonalised and exploitative way.

In the 1970s–80s, areas like Elswick and Benwell in the west of Newcastle became shorthand for deprivation in the national media. TV crews and photojournalists often visited these communities, producing bleak, disconnected images of boarded-up housing, vandalism, and youth gangs. Tabloid newspapers frequently used these images to make cheap political points, caring little for those portrayed and ignoring the criticism of local people who saw these images as selective and voyeuristic, with little regard for strong community bonds.

Though not technically ‘Poverty Porn’, in the 1990s and early 2000s, a wave of fashion and commercial photographers used post-industrial settings in northeast England for 'atmosphere'. The ‘it’s tough up North’ trope became a stylised texture for editorial or branding purposes, with photographers often using derelict warehouses, crumbling terraces, or bleak coastlines without any link to the communities that lived and worked there. Thus, working-class decline became an aesthetic backdrop that some dubbed "ruin porn" or "grime glam."

These media or commercial projects reduced poverty to a visual motif, objectifying poor or marginalised people and reducing them to symbols of misery in a way that exploited their suffering for shock, pity, or attention rather than portraying them as whole human beings in a respectful, nuanced representation.

Even in recent years, especially on social media and photography forums, some street photographers have been criticised for posting images of homeless individuals in Newcastle and Middlesbrough without consent or context, often with captions like "gritty realism" or "urban decay". These images are usually devoid of humanity, turning vulnerable people into props for aesthetic or moral effect rather than participants in their own stories.

Because for more than half a century, documentary photography has played a decisive role in preserving, interpreting, and reasserting northeast English identity, the people of the region have little truck with the exploitative outsider photographers who 'parachute' in for an assignment or two with no lasting connection to the northeast community they capture. Those who treat their subjects as passive and defeated, often photographing them without consent or involvement and emphasising dirt, hunger, addiction, or despair without exploring why or what the person's life is beyond that 'snapshot'. Some photographers sought to garner praise for their skill rather than to amplify the subject's voice, even dramatising the lighting or stylising the composition to 'beautify' suffering while ignoring social or political realities.

The accusation of ‘Poverty Porn’ often hinges on intent vs. reception. Some photographers' intent was clearly empathetic. They embedded themselves into communities, working over extended periods within that community and never treating their subjects with contempt. However, as part of a broader debate within British visual culture, around representation, ethics, and class, some viewers saw only grim images of decline, perceiving northeast England as tragic or 'othered'. Some art critics and cultural theorists during the 1990s and early 2000s questioned whether formal, carefully composed images turned poverty into a visual spectacle rather than illuminating systemic injustice. Images of unrelenting bleakness reinforcing stereotypes of Northern hopelessness rather than empowering its subjects.

Stuart Hall, the cultural theorist, framed the media portrayal of working-class people as too often filtered through middle-class lenses, which can objectify rather than humanise. Indeed, Tish Murtha, who greatly respected and admired Chris Killip, both personally and professionally, quietly (for once) but firmly insisted on the importance of her working-class roots over his middle-class upbringing. While the two shared many values: authenticity, political awareness, and a deep empathy for marginalised communities, the crucial difference in their backgrounds shaped how they approached their work. Murtha was ardent in her belief that while Killip's work had moral weight and that he "saw what others refused to see", she also felt deeply that her background gave her a different authority. And a different energy from inside the community, intending that her photographs not just document but agitate. As her daughter offered, "Tish respected Chris Killip deeply. But she believed it mattered who was holding the camera."

Chris, Tish, and the others I mentioned above were ethical social documentary photographers. Photographers who lived (sometimes for a lifetime) among and with their subjects in northeast England. Building trust and getting to know them personally. These photographers showed everyday life, not just hardship. People at work, but notably also at play. These photographers contextualised poverty within broader frameworks like unemployment, deindustrialisation, housing, and politics. Where ‘Poverty Porn’ flattens humanity into spectacle, ethical photography gives people their full weight. It listens, rather than exploits; it connects, rather than consumes.

If hard industrial labour formed northeast England's physical and economic foundation, the community was (and still is) its soul. I wrote about Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen in Byker and Beyond and how she documented the Byker area of Newcastle from within during the slum clearances of the 1970s. Her images honoured the soon-to-be displaced lives, not just recording the loss of that community life but celebrating what was still there by capturing children playing in alleyways, mothers in front rooms, and elderly residents framed in kitchen windows.

In Teesside, Graham Smith, too, explored this social fabric through intimate pub scenes and family portraits. His almost melancholic images, steeped in a longing for a culture of togetherness, warmth, and ritual, border on elegy. For Smith, the pub becomes a microcosm of working-class life and memory.

Over time, northeast England has acquired a mythic identity in British visual culture: a place of honest labour, tight-knit families, close community, robust humour, and harsh beauty. Photography both fuels and resists this myth.

On one hand, the stark imagery of decay (abandoned pits, rusting cranes, empty streets) has risked turning the region into a visual shorthand for decline. On the other hand, the more intimate and community-based work of Killip, Murtha et al allowed people to be seen on their own terms, not as victims of economic history but as makers of memory and culture.

What distinguishes the social documentary photography of northeast England is its subject matter and its listening ethic. Killip, Konttinen, Murtha et al, whether native or 'adopted' northeasterners, approached their subjects with empathy and patience. They did not impose narratives; they allowed the landscape and people to speak, and indeed their photographs have become part of the region's cultural memory. In an area so often overlooked by policy and power, visual remembrance is a form of resistance and a vital expression of identity. In every craggy face, every pit banner, every child jumping puddles outside a terraced house, there is a visual language that says: We of northeast England were here. We mattered. We still do.

Let’s turn to Mik Critchlow, who, of all the social documentary photographers, took a very long-term view and in doing so produced a masterclass in slow, intimate documentation. With his photographs of Ashington, a once-mining town north of Newcastle, and the surrounding area, Mik, a native son of the town, captured his own community going about their everyday lives.

Born into a coal mining family, Mik's grandfather worked 52 years and his father 45 years in the collieries near Ashington, so Mik grew up immersed in the mining world. However, he escaped it, leaving school at 15 to work initially as a tailor's trimmer before serving in the Merchant Navy. Then, in his late twenties, he returned to Ashington to study art history. Through this, he discovered 'The Ashington Group' (or 'Pitmen Painters') from which he took inspiration to take up photography and embarked on a lifelong pictorial documentary of Ashington and its people.

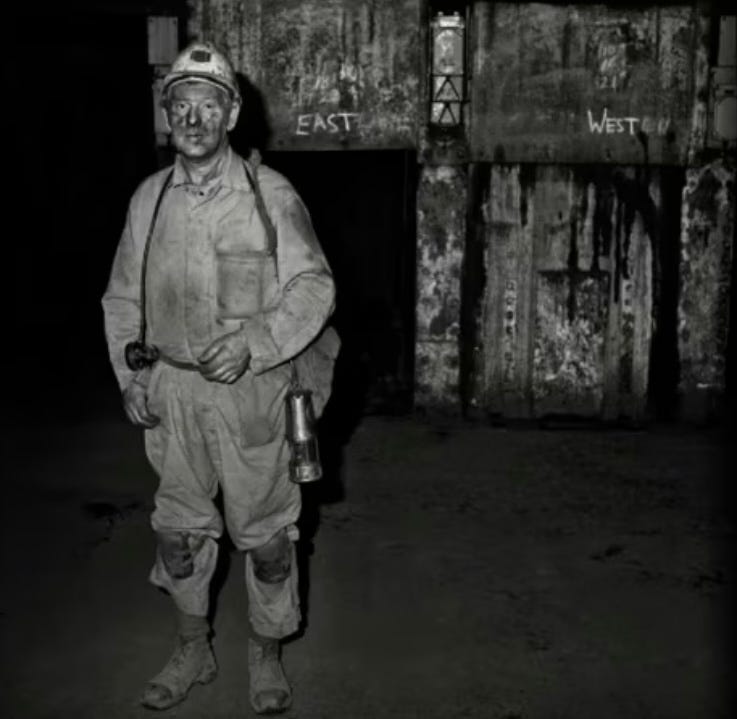

His magnum opus, 'Coal Town', a photographic project spanning over four decades, captures everyday life in Ashington from miners at work to children at play, street scenes, brass bands, bingo halls, and community events. His images reflect a deep emotional trust with his subjects in domestic scenes, striking portraits, and working lives. Notably, 'Last Man Out' taken of colliery deputy George Miller Davison, the last man from underground in Woodhorn Colliery on its final working day in 1981, is a tender memorial.

The permanent collection I looked at in what is now Woodhorn Museum and Gallery is a curated selection from ‘Coal Town’. I'm sure Mik would be immensely proud that his portraits of mining life are now on permanent display in what was once the mine where he took some of his most iconic photographs.

But 'Coal Town' wasn't Mik's only collection. There was 'Seacoalers', an intimate exploration of those individuals, to whom Mik gained access through a family connection, who harvested surface coal from northeast beaches. Mik depicting the community's resilience under economic and environmental pressure. 'Seamen' was a commission Mik received to document local merchant sailors amid union action. Mik's 'Hirst' documented an area of East Ashington, the most densely populated locality in Northumberland, where 35% of the working-age population were unemployed and nearly 40% of children lived in a household deemed in 'income deprivation'. Mik shows people navigating economic hardship and regeneration with images that blend dignity with realism, portraying community cohesion amidst change.

Comparing Mik's work with that of Tish Murtha, Chris Killip, Graham Smith, Isabella Jedrzejczyk, and Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen reveals how personal background, tone, style, and intention shape diverse ways of documenting working-class life in a post-industrial landscape.

I've mentioned that locally born Murtha's work was overtly political with photography that has edge, fire, and a sense of immediacy and resistance. She wanted to provoke, once saying, "Photography is a political tool… the only way to truly document a place is to be part of it."

She viewed her camera as a weapon against injustice, and her images were even used in parliamentary debates on youth policy. In contrast, Critchlow's work is slower and more reflective. It listens rather than declares. While equally committed to truth, Mik focused more on cultural preservation, referring to his work as "an act of remembrance." His photographs preserve a disappearing world from the inside, quietly documenting the humanity of his neighbours while also providing a quiet critique of deindustrialisation, austerity, and the neglect of working-class communities. It's photography that conveys that these people's lives mattered and are worthy of art, record, and dignity. His photographs bear moral witness, showing what happened and how it felt to live through industrial decline. In truth, Tish and Mik form two halves of a powerful northeast England visual narrative. Mik mourns the loss of what is no more while Tish demands change to what might be, using her lens as a form of social critique, capturing moments that still punch decades later. She once said, "I was trying to give them a voice. Because they didn't have one. And they still don't."

Also, in contrast to Mik Critchlow, Chris Killip's work is raw, unflinching, and emotionally heavy, with compositions often using wide angles and deep shadows to underline the gravity of decline. Killip intended to offer a deeply compassionate critique of Thatcherism and shock complacent viewers outside of northeast England into empathy. His 'In Flagrante' is iconic for its composition and stark emotional atmosphere. Killip was always conscious of the human subject amid the anguish of deindustrialisation, unemployed youth, and post-industrial decay. However, he maintained an ability to photograph the region's people from an outsider's perspective, with an objective approach. Mik's work is quieter, less visually confrontational, and more humanistic. Where Killip shows collapse, Critchlow focuses on continuity and dignity. I read somewhere that, ‘while Critchlow gives you the front room and kettle, Killip shows you the rubble and the silence after the mine closed’.

It's also important to highlight Isabella Jedrzejczyk's photographs from 1980s Middlesbrough in contrast to Mik Critchlow's work. People often overlook Isabella's work as its emphasis was on highlighting women's labour and social roles. Her photographs explore the 'invisibility' of female domestic and care work. Where Jedrzejczyk 's conceptually layered work interrogates gender, Critchlow includes women and families, but his emotional directness is within a more traditional social realist framework.

Although not from northeast England, Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen may be the closest social documentary photographer to Mik Critchlow in approach and style. Both were deeply committed to portraying working-class life with integrity and empathy, with shared subjects of community, industry, housing, and family. Although there are some contrasts, Critchlow is rooted in personal memory. In comparison, Konttinen, although intimately accepted within her adopted community, brought a fresh, analytical gaze informed by her 'outsider' status.

Critchlow also concentrated on Ashington's industrial identity, especially coal mining and its aftermath, with his later work showing the effects of long-term economic decay. Konttinen, while documenting working-class life, was more focused on urban change, housing, and the lived experience of women. Her landmark 'Byker' project was a loving, intimate record of a neighbourhood facing destruction. Critchlow's work is about continuity; Konttinen's is often about transformation. But together, the two form a vital dual lens on northeast England during a time of momentous change. Mik preserved that which lived and was lost over a lengthy period, where Konttinen captured often with urgency but grace, what disappeared almost in an instant.

So, although there are similarities and some overlap, Mik Critchlow stands apart from the other social documentary photographers because his work is less about the visual shock of deindustrialisation and more about slow remembrance. He doesn't impose a narrative; he listens to it, lives with it, and allows it to emerge on its own terms. That makes his photography more durable, intimate, and arguably more trusted by those he photographed. Critchlow's defining principle was closeness. Not just physical, but social and emotional. He didn't parachute into Ashington to shoot a project; he grew up and lived there, and his subjects were neighbours, friends, and kin. He once said, "You have to be in the tribe... you have to do the same dance."

This meant spending years on the same streets, encountering the same people, and gradually earning their trust. He didn't just capture 'events' but quiet moments of daily life: Sunday dinners, bus stops, bingo nights, working men's clubs, welfare queues. His photographs reflect people as they really were, unguarded yet dignified.

He adopted a narrative approach to curating his exhibitions by sequencing images like stories, not just aesthetic groupings. His intent was to reflect the community's pride and rhythm: work, rest, loss, play, with an emotional tone that was nostalgic but never bleak and often moved from stark reality to subtle celebration.

Mik Critchlow's powerful archive offers a valuable insight into Northumberland's lost collieries, shipyards, and seafaring. He captured with respect the everyday lives of industrial communities during rapid socio-economic change. But his work is more than nostalgia as it offers a vital record of working-class experiences in the late 20th century. His photographs intersect documentary integrity and emotional truth from inside the community. A rare and invaluable perspective.

As I've shared in an earlier Meander, to me, belonging is the emotional and psychological sense of self that is vital to an individual's well-being and satisfies the innate human need for social connection. Of being a part of something that you value and that values you. Feeling accepted, understood, supported, and included within a particular community or context. That sense of belonging can come from personal relationships and/or cultural affiliations, shared experiences and connection to a physical location. Feeling we belong offers security, validation, and a foundation for personal growth that then allows us to express our true selves and develop a sense of purpose within the context of our chosen or innate communities.

Mik Critchlow’s photographs and those of Murtha, Killip et al, remind me of where my sense of self comes from and where I belong. And that’s in a region of England once forged in heavy industry, but more importantly, amongst proud, straight-talking people forged in kinship, humour, loyalty, emotional fortitude, and a deep sense of community, especially in adversity.

An excellent analysis of the different approach each photographer had to documenting the North East. I'm not sure that I can think of any other area which has attracted so many key photographers of a generation. Perhaps it was the influence of the Side Gallery?

Wonderful read Harry. “He doesn't impose a narrative; he listens to it, lives with it, and allows it to emerge on its own terms.” Love that and you pull out the community and dignity that these folks had in a tough transition time. I grew up in Carbondale NE Pennsylvania anthracite coal. Grandfather was a miner black lung got him. High school football on Friday night is huge still and I know your community of your football club is so important to you. Thanks for your writing.