Home and Howay

A sketch, an engraving and some photographs, paintings and words...

I am a Critick, a Coal owner, a Land Steward, a Sociable Creature... One must write.

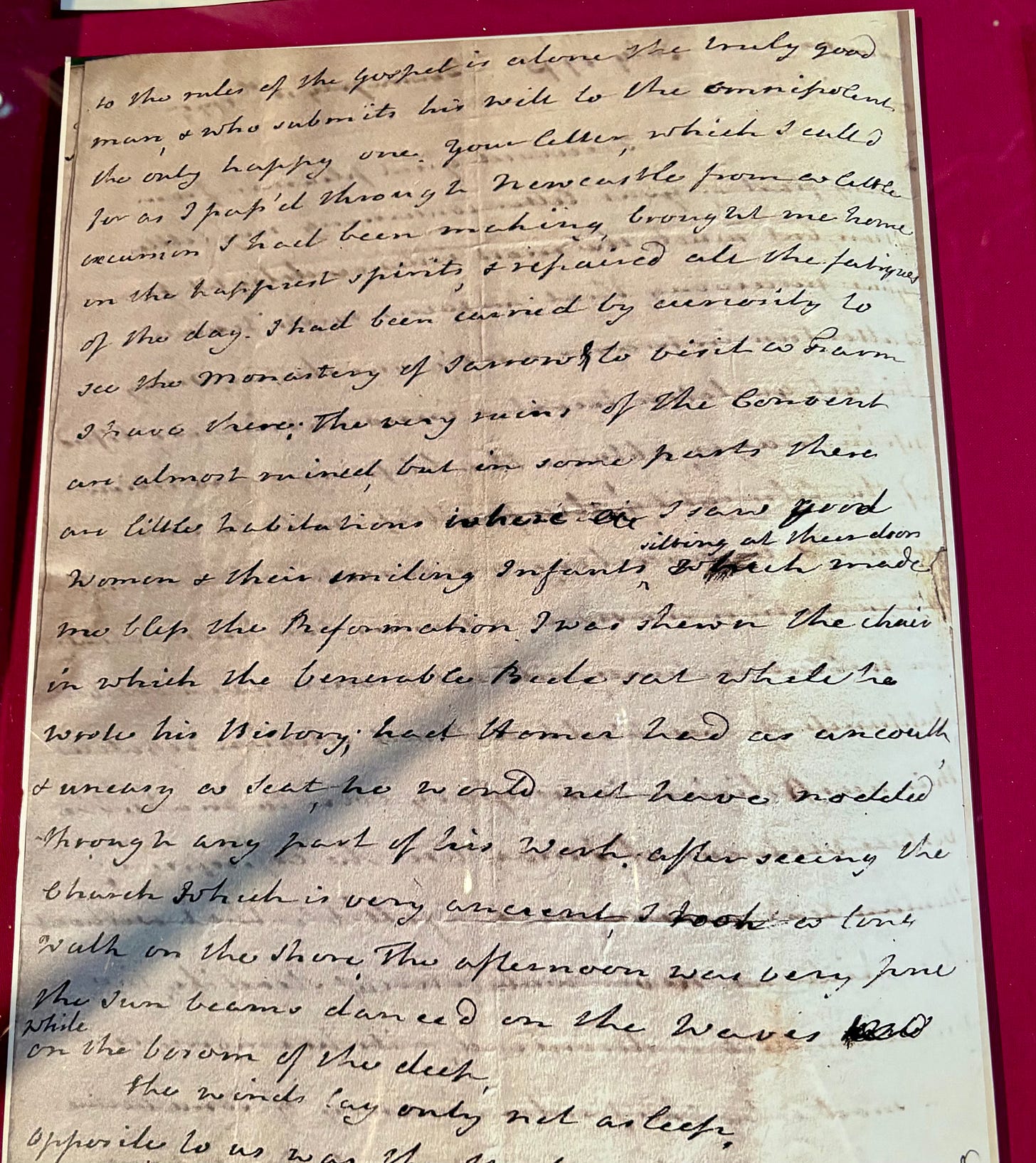

Elizabeth Montagu

I paid a visit to Newcastle Cathedral last week, not for a religious ceremony, history tour, or even a drink festival (earlier this year the cathedral held a Rum & Gin festival. There will be those who deem such events inappropriate for a place of worship, but then again Jesus did turn water into wine). No, this time it was to the 'Home and Howay' exhibition, which offered a fascinating glimpse into the growth of letter writing in the 18th century and the rise of the UK postal system.

It's easy to forget in these days of instant communication that it's not all that long ago that letters were still an important means of exchange between people, be that in their personal lives or business dealings. In 1974, when I moved to London from northeast England, I stayed connected with my parents through weekly letter exchanges. Like many people, my parents couldn't afford a telephone. Indeed, only one house had a phone on the terraced street of some thirty-plus houses, where they lived.

Unfortunately, all I have from that correspondence are a few letters from my father from the weeks before he died nearly fifty years ago. Not surprisingly, they are a treasured possession. As is the letter received by my hospitalised grandfather in July 1917, from the vicar of his hometown in northeast England, as he recovered from severe wounds sustained in the Great War. As one would expect, given the sender, the letter is one of care, compassion, and hope. It obviously meant much to my grandfather, who kept it until his death, close to seventy years later. Passed on to my mother, it came to me when she died.

In the early 1980s, business communication was still primarily conducted through letters, although fax machines were becoming increasingly common. Even then, the communication transmitted remained in the form of a letter. I recall those days of 'giving dictation' with my secretary's pencil swirling and curling across her notepad. The shorthand hieroglyphics then turned, as if by magic, into a draft letter. After tweaks or redrafts, the clean copy, as one of many such letters, was presented for my signature in my signature book. The sending of the said letters recorded by my secretary in my daybook, with anything incoming for me recorded in the post book. And then, of course, came the filing away of copies in large filing cabinets. I recall I had three for such purposes. Some colleagues had hugely elaborate filing systems. I kept mine simple. Otherwise, I struggled to retrieve anything. How did we manage without email, messaging, etc? Well, somehow, we did, and business still got done.

Anyway, enough reminiscing. Let's first deal with the words post and mail. As you'll have already noticed, in the UK, we prefer the word 'post', while in the USA, the preference is for the word 'mail'. Yet it’s the Royal Mail that delivers letters in the UK, while the US Postal Service delivers letters in the USA. Confused? You should be.

The word post stems from the Latin 'ponere', meaning 'to place' or 'to station’. England's earliest written-message-carrying service was the royal courier system, used by monarchs as far back as Henry I to send official messages via horseback between 'posts'. Places where a fresh horse (and possibly refreshment) would be available for couriers as they changed horses along their journey. Over time, 'post' came to describe the act of sending letters and packages, and the name given to the service and people responsible for this delivery, with, in 1516, Henry VIII appointing the first official Master of the Posts. Thus, a formal state service began, with 'post roads' and relay stations enabling the delivery of messages over long distances. The reign of Elizabeth I saw the system expand to accommodate message sending by both merchants and diplomats, in addition to serving the monarch. In 1635, Charles I opened the then-called 'Royal Mail' to the public, who could use this national communications service for a fee. With the restoration of his son Charles II, the Royal Mail was reorganised as a public monopoly under state control with fees based on the number of pages in a letter and the distance over which it was to be carried. Interestingly, that fee was usually to be paid by the recipient.

One hundred and fifty years later, John Palmer, the then Comptroller General of the Post Office, introduced mail coaches. These fast carriages revolutionised mail delivery times, offering a quicker, safer, and more regular service than riders on horseback, thus better supporting trade and conveying news. Such a service also encouraged personal correspondence, and just over fifty years later, Rowland Hill introduced the 'Uniform Penny Post' and the first adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black. Now you could send a small letter weighing up to an ounce (56 grams) anywhere in the UK for just one penny, making sending letters affordable to just about anyone and spurring increased literacy, especially among women and the urban poor.

The increase in sending letters led to the rise of stationery shops, letter-writing manuals, and a cultural emphasis on "good penmanship" and self-expression. Letter-writing became an emotional lifeline for separated families, between lovers exchanging declarations, and friends wishing to stay in touch. And just as we check our phones today, postal delivery introduced a regular rhythm to life with people waiting eagerly for letters in a sense of being part of a wider world, connected by a shared infrastructure.

While not an instant messaging service, it offered a fast and reliable communication system for the time. Many cities had multiple deliveries. In London, as many as twelve deliveries a day between 7:30 AM and 9:30 PM, with up to ten collections from post boxes each day. If you kept your letter short, you might exchange correspondence with someone twice or thrice a day. Exact figures for the 18th century aren't known. However, by 1850, close to 350 million letters were sent in the UK, within an estimated adult population of eighteen million.

Exchanging letters connected communities as people moved for work during the Industrial Revolution. These migrant workers could send news and wages home, easing the emotional and financial strain of being apart. And letters from migrant workers also influenced others to move, spreading knowledge about jobs and opportunities. Given that the postal system was used to distribute newspapers, pamphlets, and books, it brought national and international news to small towns and rural villages. This spreading of news played a key role in stimulating political awareness, reform movements, and spreading ideas. Being better informed, 'ordinary' people began participating more in national debates on everything from reform to civil rights. A regular postal service also stimulated trade, allowing even modest traders to connect with broader markets using the post to take orders, send invoices, coordinate shipments, and facilitate the creation of early mail-order businesses.

So, what about this word mail? The word 'originates' from the Middle English word 'male,' which meant a travelling bag or pack from the Old French ‘malle’. It became common by the late 17th century to refer to the bag for carrying letters as a 'mail of letters' and to call the coaches and boats carrying the post as mail-coaches and mail-boats. By the mid-18th century, there were references to people reading their mail, indicating the widening of the meaning from the bag to include the letters it contained. By the 19th century, people in the UK often used the word 'mail' for letters sent abroad, while 'post' referred to domestic deliveries.

As an aside, in 1890, sending a letter to a 'non-Empire' country, say the USA, from Britain cost five pennies per ounce. The cost from the USA to the UK was seven cents per ounce. The latter was a bargain, given that a pound (240 pennies) was the equivalent of nearly five dollars at the time. Interestingly, given how the exchange rate had fallen to fewer than three dollars to the pound by the early 1960s, I would still hear older people use the term 'half a dollar' as a sobriquet for a British half-crown coin (worth thirty pennies).

Anyway, enough background. Abby Hammond, a PhD student from Northumbria University, curated the exhibition ‘Home and Howay’ that features letters written by Newcastle residents during the 1700s describing daily life, business dealings, and the social structure of the time. In truth, the exhibition is a spin-off from Abby's research on women named on ledger stones from 1640 to 1815 inside Newcastle Cathedral. That work focuses on intramural burial, particularly the material culture and language of memorials, aiming to uncover the often-overlooked narratives of women commemorated within the cathedral during this period. Abbie seeks to contribute to a deeper understanding of women's roles and commemorations in historical contexts, shedding light on the social and cultural dynamics of the time.

18th-century Newcastle was a trade hub, with ships from the city travelling as far as the Baltic and the Americas. While closer to home, an important destination was London, which relied on coal from Northumberland's coalfields. With such travel, people at the time relied on letters to do business and stay connected. The rise of the postal system assisted this, and vast numbers of letters from and to people living in and around Newcastle survive in archives, giving an insight into the lives of so many. Many of these letters relate to business, arranging deals, reporting profits, or solving problems. However, trade also separated families, and there are personal letters from and to loved ones.

Letters from southern England travelled to and from Newcastle via the Old Great North Road, the historic route from London to Edinburgh. The road stretched over four hundred miles, passing through towns and cities that would be familiar to anyone travelling by train from London to Newcastle on the London and Northeast railways today: Newark, Doncaster, York, Durham, etc.

With the rise of mail coaches, the GNR became central to national communication with numerous coaching inns and post stations along the route, many of which survive as pubs or hotels even today, as much of the original GNR forms the basis of the A1 dual carriageway/motorway. While the A1 now bypasses parts of the original highway, several still serve as high streets through towns.

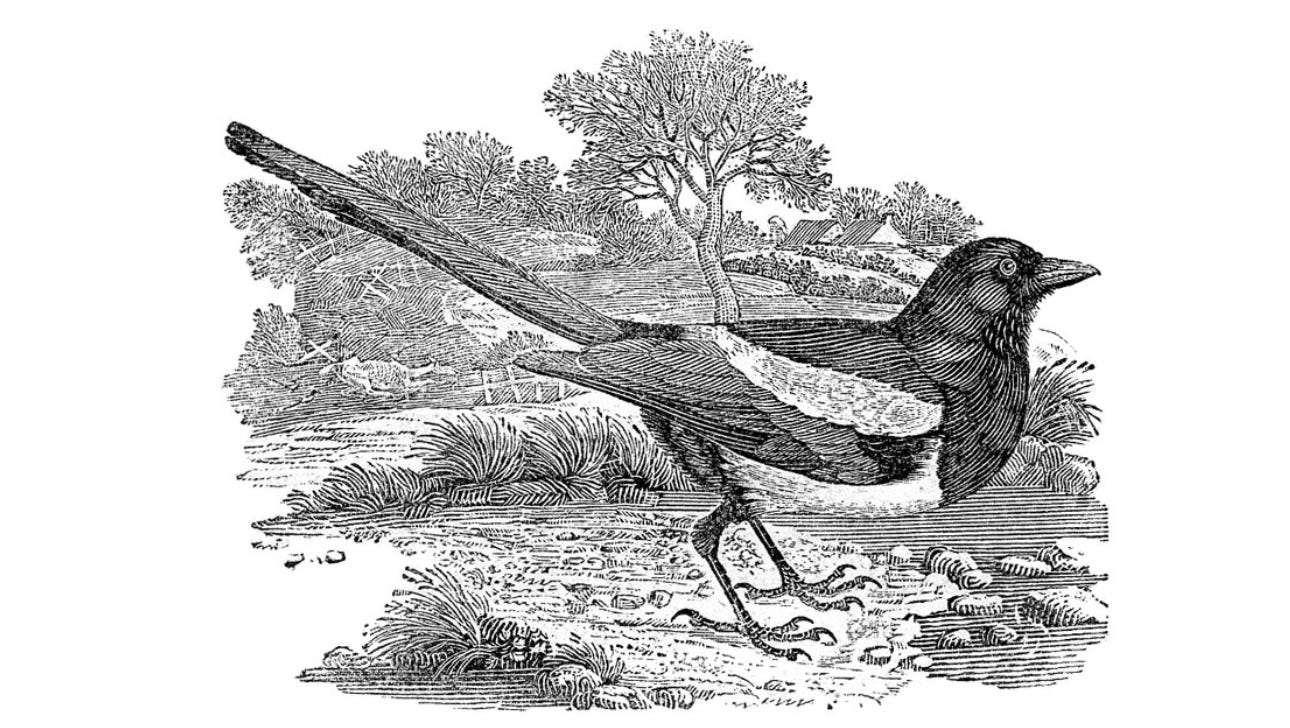

Just outside the cathedral at the aptly named Amen Corner stands Milburn House, upon which is a bust of Thomas Bewick, one of Britain's most talented 18th-century engravers. The bust marks the spot where his workshop once stood. Thomas was recognised for his strong moral sense and was an early advocate for the fair treatment of animals. He objected to the docking of horses’ tails and the mistreatment of performing animals.

During his lifetime, Thomas engraved and published many works, notably illustrating editions of Aesop's Fables. However, he is best known for his ‘A History of British Birds’, which is admired today mainly for its wood engravings, especially the small, sharply observed, and often humorous vignettes known as tailpieces. The book was the forerunner of all modern field guides. Several letters survive both to him and from him, providing insight into his life and the travels he undertook for his books.

He frequently received letters inviting him to inspect animals that individuals believed were unique enough for him to engrave. For example, one man wrote that he owned "a bull of a very curious breed" (sadly, Bewick does not appear to have produced an engraving of it).

Thomas is credited with popularising a technical innovation in printing illustrations using wood. He adopted metal-engraving tools to cut hard boxwood across the grain, producing printing blocks that could be integrated with metal type, but were much more durable than traditional woodcuts. The result was a high-quality illustration at a low price, despite some surviving letters to Thomas containing complaints about the excessive cost of his services. Other letters include apprentices requesting references and commissions for new engravings. These exchanges make it clear how vital letters were for the survival and expansion of an 18th-century creative business.

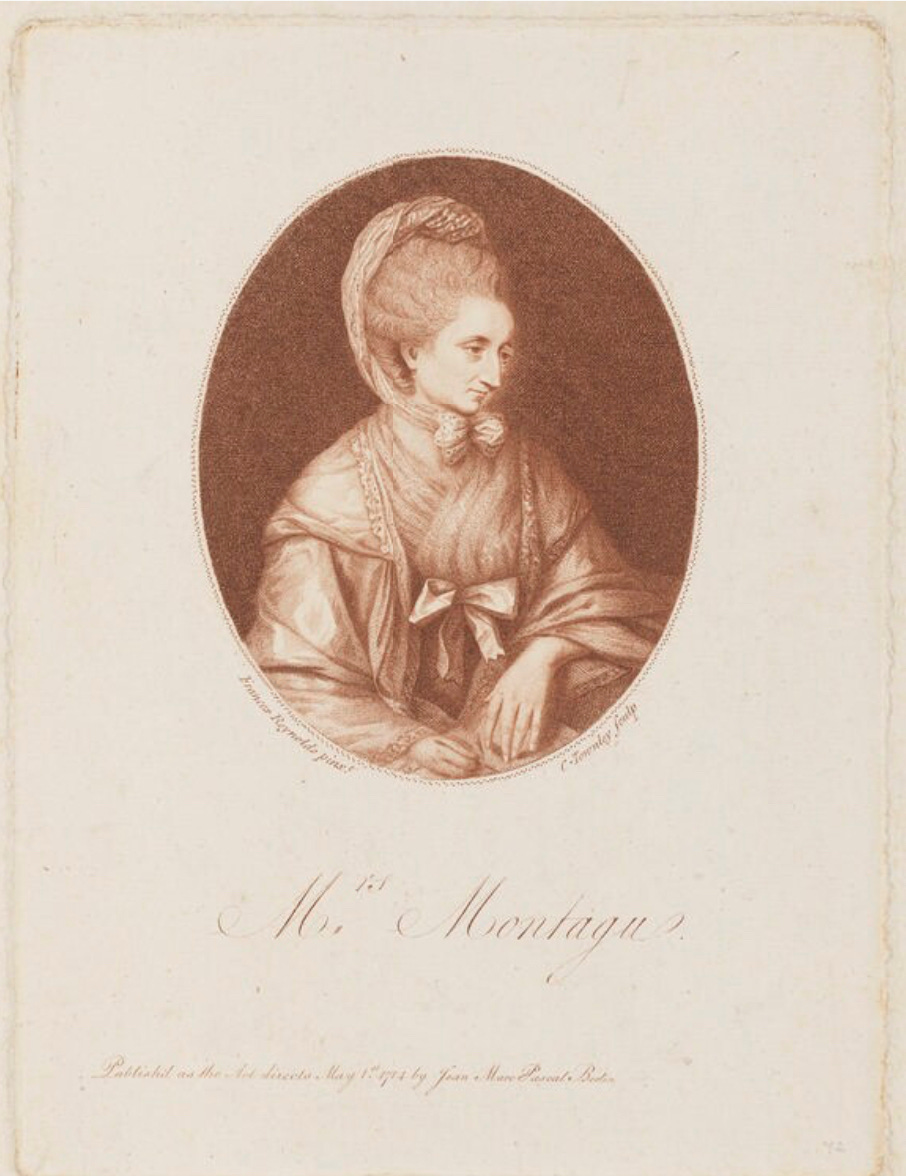

Another voluminous letter writer featured in the exhibition is Elizabeth Montagu, nicknamed 'Fidget' as a child in honour of her liveliness of mind and body. This liveliness continued into adulthood when she became well-known as a salon hostess. To modern eyes and minds, the phrase might mean something salacious however an 18th-century salon hostess was a well-educated witty, and socially influential woman who hosted gatherings in her home where intellectuals, artists, writers, and politicians came together to discuss ideas, art, literature, and politics.

These gatherings first gained significance in France where Salonnières were known for their charm, conversational skills, and intellectual curiosity as they functioned as cultural mediators, bringing together thinkers in philosophical debate, literary criticism, and discussions of current events. There might also be readings of new plays, poems, and philosophical essays and the shaping of scholarly tastes, political opinions, and scientific curiosity.

The word Salonnières originates from the salon (drawing room), the setting where informal yet sophisticated conversations occurred, blurring the line between private and public spheres as a place for the open exchange of ideas. Indeed, often more freely than in universities and the like in helping to spread new thinking about reason, science, liberty, and reform and playing a significant role in the Enlightenment through Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot, who frequently relied on wealthy hostesses for patronage and visibility.

These women greatly influenced the cultural and intellectual life of their era, creating environments for discussions of progressive ideas. In a male-dominated society, their homes were hubs for exchanging innovative thoughts.

The concept soon spread across Europe and Elizabeth already a literary critic and arts patron founded the Bluestocking Society, an 18th-century group of women and some enlightened men that discussed literature, art, science, and social reform by challenging conventional gender roles and helping create space for women's education and participation in cultural discourse.

The society derived its name from the stockings worn by Benjamin Stillingfleet, a scholar who attended gatherings. His understated blue worsted stockings, although plain for their time, ultimately came to symbolise intellectual seriousness rather than fashionable display. The society was a network rather than an official organisation, consisting of salons and gatherings hosted by learned women to promote philosophical discussion as a respectable pursuit for women while encouraging women's education, especially in literature, philosophy, and moral thought and opposing the view that women should only be concerned with fashion and society.

Sadly, over time, the term "bluestocking" eventually became a derogatory label for what some deemed 'overly intellectual' women. Yet the original Bluestockings were trailblazers in creating an inclusive culture of ideas, contributing to the rise of women's writing and the broader Enlightenment culture of the time.

Elizabeth corresponded avidly throughout her life, beginning in 1731, when she was thirteen. For the next six decades, she wrote almost daily about every topic, from health and family to politics and social events. Due to her prolific writing, over four thousand of her letters survive today, many of which pertain to northeast England, thanks to her husband's coal mines in the area. After he died in 1775, Elizabeth travelled from her home in Berkshire to Newcastle, which she describes as 'busy and smoky', at least once a year. Whilst here, her letters are of the family mining business, technology and finances. However, she also mentions the extravagant parties she held for her mining employees. Oh, and she also complained about the windy and chilly weather (no change there then)

In her free time, while in the northeast of England, she regularly explored the region in her 'post-chaise', sightseeing at places like Tynemouth Priory. It's still a wonderful place to visit today, but the title of my meander from last year, Our House on a High Rock, gives you some inkling of Elizabeth's comment about the windy northeast of England. She also attended musical performances and recitals in the town, writing back to family and friends about her experiences.

... I had been carried by curiosity to see the Monastery of Jarrow & to visit a Farm I have there. The very ruins of the Convent are almost ruined, but in some parts, there are little habitations wherein I saw good women & their smiling infants sitting at their doors which made me bless the Reformation. I was shewn the chair in which the venerable Bede sat while he wrote his History; had Homer had as uncouth & uneasy a seat, he would not have nodded through any part of his work....

Another person included in the exhibition and memorialised in the cathedral is Dr William Ingham. Born in Whitby as the son of a surgeon, he moved to Newcastle as a trainee doctor. It was not long before he gained a reputation for his surgical expertise and significant contributions to medical education in the region, treating patients across the social spectrum. William eventually became a partner to his mentor, Mr. Lambert, a distinguished surgeon and one of the founders of the Newcastle Infirmary. William later succeeded Lambert as a surgeon at the Infirmary.

William was instrumental in shaping the Newcastle Infirmary into a leading centre for surgical practice. His influence extended beyond his surgical work; he played a pivotal role in the selection of medical officers and in shaping medical policies at the Infirmary. His rigorous approach to training produced a generation of skilled surgeons who served in various capacities, including in colonial services, the military, and private practice.

Much of what we know about William comes from his surviving letters to the influential Doctor Cullen in Edinburgh, an important centre for the medical profession during this period. These letters reveal William seeking advice on the diverse conditions presented by his patients. Some of the diagnoses from his letters, such as asthma, epilepsy or ulcers, are recognisable. Sadly, some treatments failed, and women's health was particularly little understood.

After over 30 years of service, William left his position at the Infirmary. In recognition of William’s service, the governors of the infirmary commissioned a full-length portrait by Newcastle artist William Nicholson for display in the Governor's Hall of the Infirmary.

I much enjoyed the exhibition and it sparked thoughts about the historical letters I find most intriguing. For me, they’re those written episodically, as the writer incorporates new elements as their day unfolds. Reading such letters evokes a journal-like feel as you see the writer’s evolving thoughts and feelings, whether following an event they attended, a conversation, or a visit they made or received.

I've shared in another Meander that the most poignant such letter I've read is the last letter that Eileen O'Shaughnessy wrote to her husband, George Orwell. It's unfinished. Eileen began the letter to George, who was in Paris, after being ‘prepped’ for what both believed was a straightforward, albeit serious, operation. Eileen’s letter is matter-of-fact, describing the view from her hospital bed, and she comments that she will pick up the pen again and complete the letter after the surgery as if it is a temporary interruption. But, alas, that was not the case, as Eileen died during that operation, leaving her unfinished, unsent letter ending with the words, "I also see the fire and the clock".

Eileen’s funeral was in early April 1945, and some believe Orwell’s opening line of Nineteen Eighty-Four, a book he began shortly after that funeral, is not coincidental ...: "It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen."