Have you forgotten yet?

A few photographs and a few words....

Have you forgotten yet?...

For the world’s events have rumbled on since those gagged days,

Like traffic checked while at the crossing of city-ways:

And the haunted gap in your mind has filled with thoughts that flow

Like clouds in the lit heaven of life; and you’re a man reprieved to go,

Taking your peaceful share of Time, with joy to spare.

But the past is just the same--and War’s a bloody game...

Have you forgotten yet?...

Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you’ll never forget.

Do you remember the dark months you held the sector at Mametz--

The nights you watched and wired and dug and piled sandbags on parapets?

Do you remember the rats; and the stench

Of corpses rotting in front of the front-line trench--

And dawn coming, dirty-white, and chill with a hopeless rain?

Do you ever stop and ask, ‘Is it all going to happen again?

Do you remember that hour of din before the attack--

And the anger, the blind compassion that seized and shook you then

As you peered at the doomed and haggard faces of your men?

Do you remember the stretcher-cases lurching back

With dying eyes and lolling heads--those ashen-grey

Masks of the lads who once were keen and kind and gay?

Have you forgotten yet?...

Look up, and swear by the green of the spring that you’ll never forget.

Aftermath by Siegfried Sassoon

Today, we observe Armistice Day in the UK and Commonwealth, a significant day in the calendar when at 11 am, many of us pause to remember the service and ultimate sacrifice of all those, regardless of their uniform, who defended our freedoms and protected our way of life. This includes those who fought against would-be invaders or terrorists, as well as the civilians who have lost their lives to conflict or terrorism. This week’s meander is therefore a solemn one, likely to evoke various emotions and indeed disagreement. I recognise that the tradition of wearing a poppy in the run-up to Armistice Day is fading, as many view it as glorifying war.

For me, it reflects remembrance of the horrors of conflict, and indeed, the poppy has symbolised death for over two millennia. Long before it became a specific emblem of war remembrance, inspired by John McCrae’s poem. The red poppy was linked to sleep, death, and resurrection in ancient Greece and Rome. The flower was associated with the twin brothers in Greek mythology, Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death), and its sedative sap (the source of opium) symbolised eternal sleep. The Romans used poppies in burial rites and carved them on tombstones to symbolise rest and the afterlife. While in medieval Christian art, red poppies sometimes appeared in depictions of the Crucifixion, symbolising Christ’s sacrifice and blood.

In folk traditions, poppies grew on disturbed ground, often around battlefields and graveyards, reinforcing their link to death and renewal. The phrase “sleeping like the poppies” appears in some 18th and 19th-century poetry as a gentle euphemism for death.

And, of course, in buying a poppy, you are doing more than just remembering the dead from conflicts many decades ago. You are giving to charity, the Royal British Legion, which offers financial assistance, rehabilitation and recovery services, advice on benefits, housing, employment, and companionship and care homes for elderly veterans. The RBL also addresses modern challenges like PTSD, homelessness, and the needs of younger veterans. In the past, I volunteered as a poppy ‘seller’ and was moved by people's generosity for that cause.

Not all war casualties wore military uniforms, so wearing a poppy is my way of remembering people like Edith Cavell, Noor Inayat Khan, Harry Farr, and the other 305 men wrongly executed by firing squad during the Great War. Indeed, I wear my poppy in remembrance of all, be they military or civilian, of any sex, religion or belief and all nationalities that have lost their lives to military aggression or terrorism. I wear it in keeping with the phrase ‘Lest we forget’ because if we do forget, then, to paraphrase George Santayana, it condemns us to repeat that which we forget. However, when we look at the conflicts and acts of terror that continue all over the world, it seems many choose to forget and are hell-bent on repeating the horrors. Some reading this will, therefore, think that wearing a poppy means I am simply naive. That may be so, but there are far worse things to be than naive.

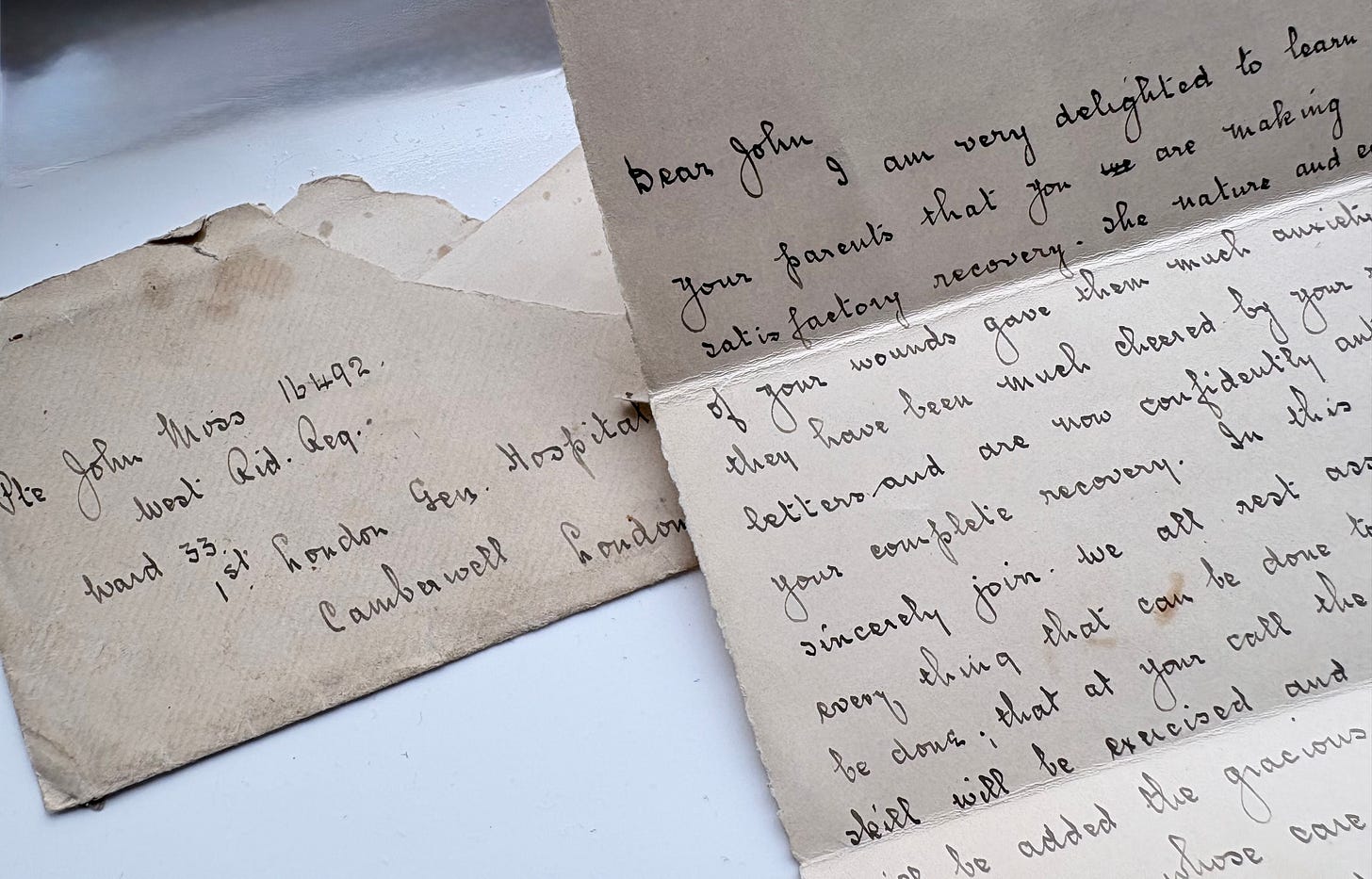

I’ve mentioned in previous Meanders that during my later years of working, I had the honour of taking part in several of my then-employer’s remembrance activities. One year, I gave a talk on the history of poppy-wearing. Very much seen as a British symbol today, but its first shoots were in the USA. On another occasion, my subject was ‘My family at War’. As the title suggests, it was my family’s involvement in the Great War, the Second World War, and later, in what we used to call peacetime.

Those regular readers of my Meanders will know that my then-20-year-old grandfather, a coal miner, left the mine to answer the call to volunteer for the Great War. Tens of thousands of coal miners did so at that time (in 1914, coal mining was not a reserved occupation; that changed the following year, when production fell sharply). I suspect they shared my grandfather's views that it wasn't driven by patriotic fervour or deep hatred for Germans, but simply because army pay was more stable than the piecework wages from private mine owners. My grandfather also thought the trenches would be no more dangerous than working deep underground. He was correct about the pay but not the trenches.

My grandfather joined the 10th (Service) Battalion of The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding), known as the 10th Dukes, rather than the more local Durham Light Infantry or Northumberland Fusiliers, because the regiment had a distinguished name. I also know he joined up shortly after Lord Kitchener's call for volunteers in September 1914 and woke up on the floor of the Sheffield barracks on his 21st birthday after celebrating the night before.

Arriving in France in late August 1915, the 10th Dukes first saw action around Armentières. They also fought in the Battle of Albert in July 1916, which was one of the initial phases of the murderous Battle of the Somme. However, fortunately for him, they were not in the infamous first wave of the attack, being involved in later assaults near La Boisselle and at Contalmaison. Nevertheless, my grandfather mentioned that the regiment still suffered heavy losses.

It was just before the opening of a battle that would prove a success for the British, the Battle of Messines, in June 1917, that shrapnel from an artillery shell seriously wounded him. The path it tore along his leg, arm and jaw was still obvious some fifty years later. Indeed, his jaw needed rebuilding, which involved fitting a metal brace inside his mouth as the jaw bones reset. He kept that brace as a sombre souvenir. His injuries meant it was the end of his fighting days, so after recovering from his wounds, he was back down the coal mine for the next forty years. His brother was not so lucky. Wounded fighting in the Dardanelles, he later succumbed to infection in those wounds.

My grandmother’s (although at that time she and my grandfather had not yet met) Great War effort was as a ‘canary’, the nickname given to munition workers, because prolonged exposure to cordite caused their skin to turn jaundiced. When the Second World War broke out, my mother, who had just turned sixteen, hoped to join the Women’s Royal Army Corps. Alas, her flat feet scuppered that, so she followed my grandmother’s example and began work as a canary. It was a dangerous occupation, and in later years, my mother recounted several stories of accidents leading to injury and, on occasion, death of the women (and it was almost all women) who worked in that occupation. Fortunately for her (and me), she came through her five years of service unscathed.

My father was a firefighter when the Second World War broke out, and once the bombing of cities began, he was kept quite busy! It’s not widely known that firefighters moved from other parts of the country to London at the height of the Blitz, in my father’s case, to a station on the Euston Road near Euston railway station. It remains an operational station for the London Fire Brigade today. Whenever I pass it, it calls to mind those ‘angels with dirty faces’ and my father’s stories of fighting fires through the war. Being a firefighter is a dangerous occupation at any time. Still, it doesn’t help when someone is also intent on dropping high explosives or incendiaries on you at the same time you are going about your day job. Again, fortunately for me, he, too, came through his wartime experience unscathed.

Throughout his life, he maintained deep respect for the Salvation Army. Not through any religious beliefs but because when the bombs were falling and the firefighters, Air Raid Patrol wardens, and other emergency services were looking to save lives, it was the good old volunteer Sally Ann’s who were alongside them, sharing the danger, helping survivors, and feeding the emergency services workers.

When the Second World War broke out, my grandfather was in his late forties and joined the Home Guard. The TV comedy series ‘Dad’s Army’ now defines that organisation in many people’s minds. Unlike many who watched it, my grandfather did not like the show. He was proud of his service and felt the TV show ridiculed those willing, whatever their age, to defend the country against invasion. On the other hand, my father felt a grain of truth was running through the programme, given some of the antics he knew the Home Guard indulged in. I’ve always found Dad’s Army funny, but as I much loved my grandfather, I never shared that with him. And we must remember that should Hitler have successfully invaded the UK, it would have been to people like my grandfather and the other veterans and youngsters that the country would have turned.

My brother and sister joined the Army in the 1960s, supposedly in ‘peacetime’. Yet that ‘peace’ still saw my brother serving in what, at the time, were hotspots like Aden, Singapore, and Northern Ireland.

Growing up with a brother and sister in uniform and visiting them regularly gave me an early understanding of service life. I also gained an early insight into terrorism when I moved to London in 1974, just as the Provisional Irish Republican Army began its bombing and shooting campaign there. As forensic scientists, PIRA regarded my colleagues and me as legitimate targets, so if we received a telephone threat using the correct code word while in the lab, we knew exactly what action to take.

That action was a calm evacuation of the lab, taking with us whatever evidence the mischief-makers would wish to see destroyed. Once the building was empty, the relevant military service then swept it to seek out any bombs planted.

We received such calls several times during the PIRA campaign, but no bombs were found. At that time, we speculated about the purpose of such calls. Might someone watch the evacuation to pick up details on the timings and what we carried from the building? Or to identify particular people. Or was the aim to try to sneak someone in when we re-entered the building? Difficult with the ID checks each of us went through before gaining re-entry.

Our evacuation area was the ‘Bullring’, now occupied by the IMAX cinema close to London’s Waterloo railway station. Back then, we occasionally played football there during lunch breaks, as well as it being our designated evacuation area.

My experience was nowhere near the level of danger my grandparents, parents, and siblings faced. Still, it did make me realise that no matter how ‘innocent’ you perceive yourself to be, some malcontent might perceive you as a legitimate target.

And returning to Armistice Day, I have attended many moving Armistice Commemoration ceremonies over the decades. For some years before leaving the northeast of England in 1974, I stood amongst those like my grandfather who knew what it was like to go ‘over the top’. To run and, sometimes under orders, to walk towards the guns. Who saw friends and comrades killed, sometimes when only a few feet from them on the battlefield. Yet their stories were more of the lice and mud and dodgy grub than acts of bravery or sights of horror. I guess, in their case, to remember was still a little too fresh in their minds. And there were men from the Second World War too, who musing over a drink after the ceremony offered the black humour of old service personnel rather than the derring-do of running up shallow beaches with bullets fizzing past, jumping out of burning tanks or the joys of standing up to their waists in the Channel hoping for rescue off the coast near a little place called Dunkirk. These rheumy-eyed men had decades ago, at an age not much older than I was at the time, ‘done their bit’ and now lived in the hope they would be the last called upon to do the same. You might say they were as naive as I am.

Back in 2010, I found myself on business near Waterloo Place in London. It was September 15th, Battle of Britain Day, and as I strolled down Lower Regent Street, I was struck by a group of older gentlemen gathering together. Many were physically challenged, but what caught my eye were the young serving members of the RAF who stood companion to each of them.

It didn’t take me long to discover they were congregating to witness the unveiling of the statue to Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, who commanded the 11th Group of Fighter Command, which successfully defended London and South East England during the Battle of Britain. Responsible for the hour-by-hour decisions of the group, New Zealander Keith Park epitomised the role played by those from Commonwealth and other allied countries who stood alongside British forces in saving the nation from invasion.

And those older gentlemen who congregated that day were the remaining few of ‘the few’ that Keith Park once commanded. As I watched for a while, I was deeply moved by the stark contrast between the veterans now stiff of limb, who had risked their lives 70 years earlier, and the younger RAF members in their pristine uniforms, showing their utmost respect for those who were willing to risk all.

During my career in Aerospace and Defence, the Armistice ceremonies I attended took on a more military flavour with ramrod lines of serving service personnel, crisp salutes and beautifully plaintive recitals of the ‘Last Post’. But the most evocative for me was after my retirement when, for a few years, I was a volunteer reader at a primary school, helping six and seven-year-olds develop their reading skills. One year, Armistice Day fell on one of their school days. So, at 10:45, all the children, toastily wrapped up against the cold November chill, assembled on the ‘parade ground’ (usually known as their playground). Class by class, each child carefully placed their handmade paper poppy on a grassy bank beside the playground, then returned to line up in rows. Rows that were a bit straggly, and yes, there was some shuffling and whispering in the ranks, and yet when the school bell sounded at 11 am, every child fell silent and stood stock still for two minutes. A task that takes much concentration for those so young. As I stood silently with the children, their teachers, proud parents, and grandparents, some with handkerchiefs discreetly in hand, I glanced up at the fluttering red paper poppies. I thought about my grandad and his old comrades and pictured the smiles they might wear if they saw this scene.

Lest we forget.

I don't know which station he served at, but it would have been around Euston area. He mentioned some friction between the two brigades. He wasn't too keen on the senior officers of the national brigade, but liked the firefighters.

Another good read, thanks Harry.....my maternal grandad was part of the BEF, one of the 'old contemptables', there from day one, through to 1919. My paternal grandad was in the London Fire Brigade, and worked alongside the National Fire Brigade, during the Blitz. He was also in the Salvation Army band, I wonder if they ever crossed paths.....