Dance to thy daddy, sing ti' thy mammy,

Dance to thy daddy, ti' thy mammy sing;

Thou shalt have a fishy on a little dishy,

Thou shalt have a salmon when the boat comes in.

From ‘When the Boat Comes In’ (or ‘Dance Ti Thy Daddy’), a traditional Northumbrian folk song with lyrics believed written by William Watson (no relation) in North Shields around 1826.

Last month, I shared in a couple of Meanders a ‘potted’ history of the northeast England town of North Shields, which this year celebrates its 800th anniversary. As part of that celebration is a photographic exhibition, 'Harvest of the Deep', of the work of local photographer Pete Robinson that brings to life the harshness and dangers of the fishing industry while offering character studies of those who ply their trade that way. Inspired by photographer Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, who documented Byker in the 1970s (see my Meander Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen - Byker and Beyond,) Pete wanted to capture the North Shields fishing community, before it disappears, as a visual story of the fishing 'journey' from boats leaving port to the fishmonger's counter, highlighting the hard work, tradition and character of the fishing community of North Shields.

In other Meanders, I've shared the importance of fishing to the economy of the northeast England coastal towns and indeed the founding of North Shields (and the ultimate derivation of its name) all those centuries ago as a settlement of ‘shiels’, simple fishing huts on the north bank of the Tyne, under the protection of the Prior of Tynemouth.

For close to the next four hundred years, fishermen from North Shields, using small open boats, fished for herring, salmon, and flatfish, and despite the best efforts of its larger neighbour Newcastle to limit the town’s trade, North Shields developed quaysides, net-mending yards, and smokehouses. By the 17th century, some North Shields fishermen still used the traditional coble fishing boat to catch fish closer to the shore, while others from the town worked larger vessels out into the North Sea to catch herring. Sometimes as far as the Dogger Bank, a one hundred and sixty miles (two hundred and sixty kilometres) long and sixty miles (ninety-five kilometres) wide underwater area of raised sand in the North Sea, lying over one hundred miles (one hundred and sixty kilometres) east of the Northumberland coast. While much of the North Sea is up to three hundred and twenty feet (a hundred metres) deep, the Dogger Bank is shallower, at often just fifty feet (fifteen metres), which makes it rich in nutrients and fish and one of the most important fishing areas in Europe for the catching of cod, haddock, plaice and herring. The name comes from the Dutch word 'dogger', a fishing boat used in the Middle Ages to catch cod.

By the 18th century, herring was the most abundant fish landed at North Shields and central to the town's trade, with barrels of salted herring exported to London, the Baltic, and even as far as the Mediterranean. Line fishing for cod was also widespread, particularly on the Dogger Bank. Local people bought fresh cod with the surplus salted and dried for longer-distance trade. Haddock was another staple landed and was popular for local consumption, as was whiting (still my favourite white fish). Flatfish (plaice, flounder, sole and turbot) caught in the shallower coastal waters went to Newcastle's markets. On a smaller scale, some fishermen gathered shellfish (lobsters, crabs, mussels and oysters) to be sold locally.

These 18th-century fishermen from North Shields displayed remarkable bravery when they ventured far out into the North Sea on long and dangerous voyages. Late in that century, fishermen sailed two-masted ketch-rigged vessels to reach the Dogger Bank. Without modern charts, skippers relied on dead reckoning, lead lines, and their experience of tides.

At that time, a voyage would typically take over a week, with the vessel carrying six to eight men and provisions of bread, salted meat, dried peas, beer or weak ale with fresh water in casks. Only powered by sail, the vessel relied on the west wind to push it towards the Dogger Bank. The skipper was usually steering while some crew trimmed sails. The men slept in shifts on straw bedding in the cramped cabin, and while not working the boat or asleep, they would be busy baiting the lines with mussels or pieces of fish.

Given a favourable wind, the vessel should be over Dogger Bank around the third day out, with the skipper judging that using a lead line to confirm the shallower depths. At this point, 'long-lines' with hundreds of baited hooks were set out and left to sink. Around twelve hours later, the men would haul the lines in. Over the next three days, the fishermen repeated the process, or if herring shoals were sighted, drift nets were set overnight, lit by lanterns on floating buoys. Processing the fish caught happened immediately, with cod split and salted, and herring piled in barrels with coarse salt. The work was monotonous but exhausting: baiting, hauling, gutting, salting, then, as necessary, mending gear with hands that were now raw and salt-cracked.

Of course, being in the North Sea, a squall could easily blow in, usually from the northeast, with waves breaking over the deck while men lashed barrels and gear to keep them from washing overboard. All was good if they rode it out, but if the vessel foundered, their chance of survival was slim. Even if they survived a storm, it would leave the men soaked and weary. Nevertheless, they would need around three fishing days to maximise the catch before, with provisions running low, it was time to turn for home and the hope that in a couple of days, they should be back in North Shields. Today, it's often said that traffic accidents happen at the end of the journey when you are close to home and your concentration drops. The same would be true of these fishermen because, as they approached the Tyne, they needed to avoid the Black Middens rocks and the sand banks at the mouth of the river with only the meagre light from the ‘High’ and ‘Low’ lighthouses to guide them.

Even close to home, danger was never far away, as in the Coble disaster of 1848, when a violent gale struck the mouth of the Tyne and capsized several boats in sight of the shore. Over one hundred men were lost, leaving many families in North Shields without their breadwinners.

A Dogger Bank trip from and to North Shields was gruelling, dangerous, and uncertain. Once at the Bank, the rhythm was unchanging: bait, set, haul, gut, salt, repeat. The men lived with cold, wet, hunger, and fear of storms, yet they persevered. There was little other employment, and a good catch would mean a good return for the men and thus their families.

By the middle of the 19th century, the arrival of the railways transformed the North Shields fishing trade, with the town becoming one of England's most important fishing ports. Fresh fish could now be sent rapidly to London's Billingsgate Market and other cities' markets. There are records of North Shields men telling stories of how fast the fish had to be packed in ice and loaded, sometimes working through the night to meet the train so that a fisherman's catch could be served in a London restaurant the next day.

The industry also expanded to include dozens of steam trawlers, venturing further into the North Sea while prawns and lobsters joined herring, cod, and haddock as staples. This expansion also saw rope makers, net factories, boat builders, coopers (for fish barrels), ice merchants, and smokehouses grow up near North Shields' Fish Quay.

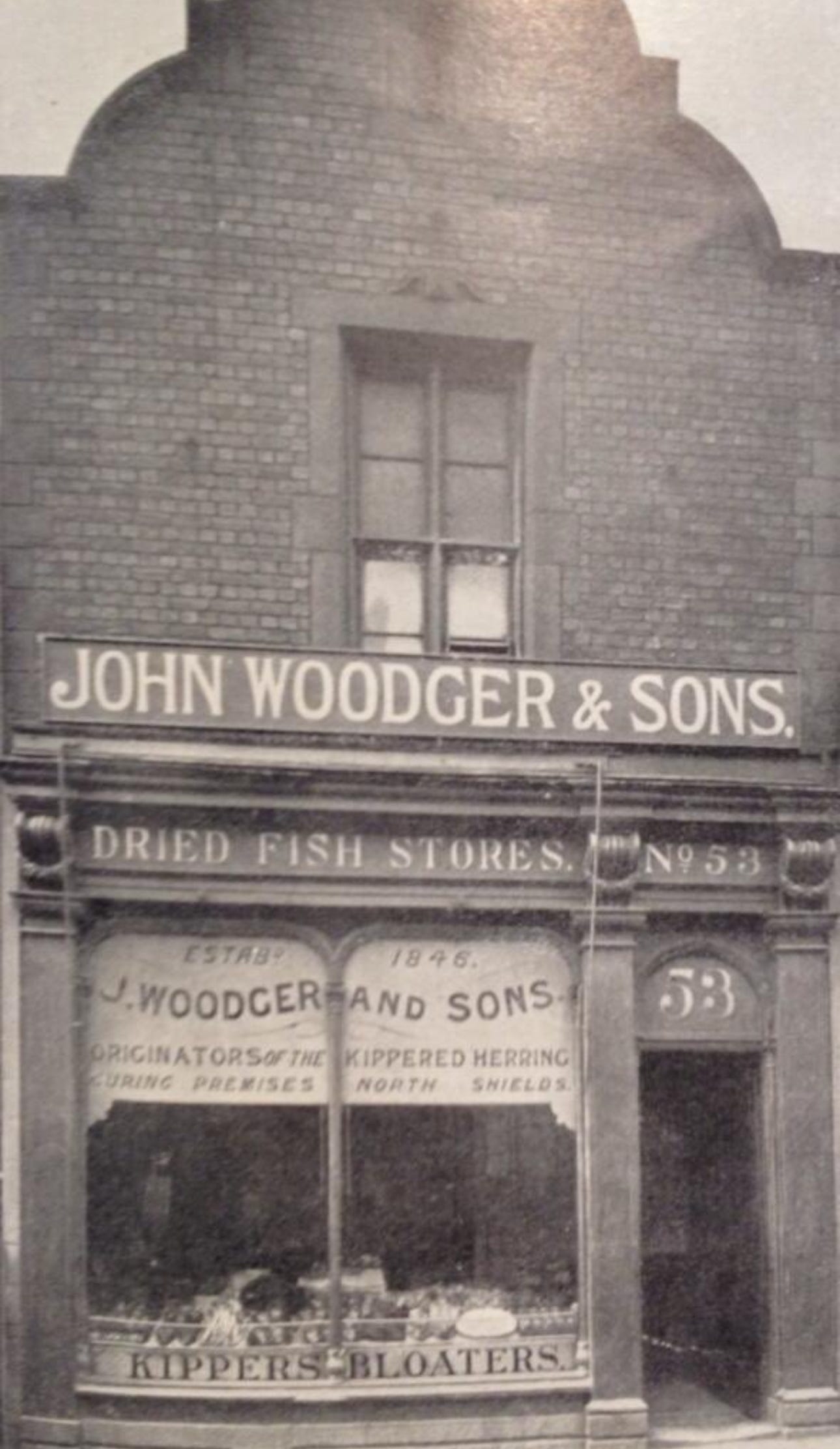

The herrings were kippered (split open, gutted and salted, then smoked over oak chips or sawdust) at the fish quay. A Newcastle man, John Woodger, who ran a fish-curing business in North Shields, claimed to have invented the process in the second half of the 19th century. A sign in the shop window proudly stated, 'The Originators of the Kippered Herring'. John claimed that when he worked in Seahouses (a coastal town some miles north of North Shields) in 1843, he'd accidentally left some split salted herring in a shed where a fire had been burning overnight. On discovering his mistake, his first reaction was that the smoke must have ruined the fish, but after he tasted it, he changed his mind. Of course, he wasn't the first to smoke fish; smoked salmon was already a popular meal. However, John claimed to be the first person to split a herring along its back (not the belly), then soak the cleaned fish in brine for up to twenty hours before smoking them. Of course, it's impossible to prove (or not) that John was the first person in the world to produce kippered herring. But it was undoubtedly a neat bit of marketing, and his business thrived. Consignments of his kippers were sent from North Shields down to London, and given the level of trade, John could afford homes in Newcastle and Great Yarmouth.

By the Early 20th century, North Shields was at its busiest as one of the largest fishing ports in Britain, second only to places like Hull and Grimsby, with fishing shifting from sail-driven long-liners and cobles to an ever-expanding fleet of steam trawlers. At the outbreak of the Great War, North Shields had over three hundred and fifty trawlers working out of the Fish Quay, along with many smaller vessels. It was recorded that over four thousand people were employed in the fishing industry locally (crews, fishwives, coopers, netmakers, and others). The steam trawlers went to the Dogger Bank, Farne Deeps, and as far as Icelandic waters, staying out for days or weeks while Drifters worked the herring season and inshore cobles supplied fresh fish daily to the Newcastle and Durham markets.

However, the Great War devastated the fishing fleet, with many trawlers requisitioned by the Royal Navy as minesweepers and patrol boats, and dozens lost to mines, U-boats, and storms. The losses meant the fishing fleet never quite recovered its pre-war numbers. However, fishing remained central to North Shields' life, with many boats landing daily catches and the local fish market bustling with traders. Then came the Second World War, and again parts of the fishing fleet were requisitioned and many fishermen called up for the Royal Navy.

After the Second World War and despite losing vessels and men, a significant fishing fleet continued to operate from North Shields until the 1960s. However, that fleet was under increasing pressure from overfishing and foreign competition.

Then came the rapid decline of fishing out of North Shields due to the Cod Wars, the introduction of fishing quotas, and the overall depletion of North Sea stocks. By the mid-1980s, large-scale commercial fishing out of North Shields had largely ended. Fish are still landed today, though now on a far smaller scale, and it’s mainly family-owned day boats that ply their trade, bringing in shellfish, prawns, and lobster.

Although there is no longer the proliferation of boats, Pete Robinson’s photographs tell the story of North Shields' fishing industry over the past decade in 'The Harvest from the Deep' exhibition. North Shields-based Pete trained in photography in the Royal Air Force at the Defence School of Photography and after leaving the service became a professional photographer. During this project, Pete built relationships with the town's fishing community, capturing some 10,000 images out at sea and on the quay, following the process from the boats leaving port to the selling of fish at the fishmonger. Pete’s photographs, in black and white and colour, capture the long hours, harsh conditions, close working relationships, and the love of working at sea.

The exhibition was funded by North Shields Cultural Quarter, which is part of North Tyneside Council's ambitious plans for North Shields to enhance and grow the creative economy. The exhibition takes its name from the Latin motto for the old Tynemouth borough coat of arms - Messis ab Altis - Harvest from the Deep, referring to the area's fishing and coal mining heritage.

Pete self-published a photo book to accompany the exhibition, with all proceeds donated to the Fishermen's Mission in North Shields and The Old Low Light Heritage Centre. Pete said: "Photographing the North Shields fishing industry has been an absolute labour of love for me over the past ten years, and I've spent a lot of time getting to know the fishing community. Instead of presenting the photos in date order, I'm using them to tell a story, starting with the boats heading out, then hauling in the catch, landing it, the workers at the prawn processing factory, the sales at the fish market and following it right through to the fishmongers. It's a photographic narrative [with] little details like a pan of porridge on the onboard stove, a tattoo, a St Christopher for protection, beautiful sunrises, memorial plaques to those lost at sea while fishing off North Shields, reminding us what a dangerous job it is working in the UK fishing industry. The photos … all capture a moment in time, whether it's the men bringing up crates of prawns, lowering lobster pots, mending the nets or sorting the catch. Some are men out fishing by themselves, including a 79-year-old lobster fisherman … One man has worked on the Fish Quay for 65 years. He remembers the steam-powered trawlers in the 1950s. He doesn't want to retire; he loves it so much. But it's an ageing workforce, there aren't many young ones coming through."

Diane Wailes from 'I Love North Shields' wrote the introduction to the 'Harvest from the Deep' book. "North Shields is changing and changing fast. The fishing industry is under enormous pressure and some of the people and activities that make North Shields Fish Quay such a vibrant and unique place may not be around in ten or twenty year’s time … Like all the best documentary photographers, Pete has taken time to get to know the people he photographs, going out with them on fishing trips for ten hours or more, with painfully early starts, rough seas and seasickness to contend with, in the search for images that capture the harsh realities and camaraderie of life at sea. Photographs that are so evocative you can almost feel the cold, and smell the heady mix of fish, prawns, diesel and cigarette smoke."

And the exhibition doesn't just include Pete's work. In 1979, Side Gallery commissioned Nick Hedges to document the fishing industry in North Shields, creating a series that captured the daily realities of those who worked on the fish quay at that time. His photographs also followed the process from sea to market, showing fishermen's labour, the demanding conditions on trawlers, and the land-based trades that supported the industry. Rather than focusing on a romanticised view of traditional fishing, Hedges' work presented a detailed and unsentimental account of an industry during economic and social change.

Hedges was a remarkable photographer, best known for his work with the housing charity Shelter in the late 1960s and early 1970s. These photographs helped to expose the slum housing crisis in Britain and played a key role in transforming public and official attitudes towards these terrible living conditions for those at the bottom of the social ladder.

Hedges 'The Fishing Industry' showed an industry that consumers rarely see and few think of the work and danger that goes into their daily catch. He captured stoic men in Fair Isle jumpers wading out to their boats, sailing into stormy skies, hauling nets, knee deep in their catch. The beauty of Hedges' images is their stripped-back simplicity, but at the same time, what they reveal about this kind of work. One man leans casually on the inside of the boat with his back to the camera. Dozens of gulls menacingly hover above his head, ready to swoop, holding position against the wind and the waves as he guts the fish and lets them fall to his feet. This is hard, isolated work.

Other photographs are back on land with fish neatly packed into boxes at the auction on the fish quay, men eyeing up the catches and smiling, jostling with one another. It is not just the fisherman and their catch on show; we also see other aspects of this industry. A woman walks carefully across the factory floor with a steaming block of fish. A man stands legs astride in a smoke house, handling neat rows of kippers on sticks. Huge blocks of ice are handled with giant pincers in a large shed, glowing in the light, with people almost treating them as if they are hot, not cold. A commentator at the time said, 'fishing is the closest thing Britain can offer to the Gold Rush towns of the Wild West', and we certainly see all the characters here that this example evokes.

Pete wanted to include some of Hedges' work because both he and the Side Gallery had been major sources of inspiration for Pete’s documentary photography. He believed that his 'Harvest from the Deep' project would not have been possible without them.

Pete discussed his project with Hedges, who was a great support, especially with the narration part of the book. Sadly, Hedges passed away in June this year at the age of eighty-one, and Pete felt it more important than ever to celebrate Hedges’ work at Fish Quay and to bring some of it back to North Shields, where he captured it over 45 years ago.

I'll leave this with Pete’s words on the lives of the North Shields fishing community, "These sort of people and stories won't be around forever so I'm trying to capture as many people and as many stories as I can for future generations to enjoy ….when you fast forward twenty to thirty years, the type of work might have changed, the type of fish might have changed. The fish quay will probably have got smaller again. It's important to capture these people and stories before they're gone forever."

Mr. Cullen looks like a Gold Rush era miner 49er, actually ! I can well understand how the sea can get in one's blood / DNA. I came from a naval family although I was unfit ( ? ) to join.