Gibside

Some photographs and some words...

We all want quiet. We all want beauty... We all need space. Unless we have it, we cannot reach that sense of quiet in which whispers of better things come to us gently.

Octavia Hill - Co-founder of the National Trust Charity (along with Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley)

Last week, I took the bus from my home in Blaydon a few miles south down the River Derwent Valley to an adjoining English County that labels itself the 'Land of the Prince Bishops'. I don't expect those who live overseas to know that county's name, but I hope that UK (or at least England)- based readers would know which county that is.

My destination was Gibside, a remarkable 600-acre National Trust estate near the village of Rowlands Gill (pronounced with a hard G). Gibside (also pronounced with a hard G) is a popular destination for those who wish to explore architectural grandeur and a picturesque landscape that encapsulates centuries of British history, wealth, power, and societal changes.

While coal mining in northeast England has existed since Roman times, the Industrial Revolution drove up demand massively. Until the 18th Century, the Derwent Valley area was rural, sparsely populated and primarily agricultural, dotted with small hamlets or villages such as Rowlands Gill. The village takes its name from a 'Gill', a Northumbrian term for a stream running through a steep valley or ravine. In this case, the stream is the Spen Burn that runs into the River Derwent.

The first mention of Rowlands Gill was in 1728 as Rowland Richardson's Gill and of a bridge that spanned the Gill. There is no record of who Rowland Richardson was or if Rowland still owned the land the bridge crossed. The document that mentions the Gill is an agreement to maintain the waggonway across the bridge, indicating the transport of coal and thus its mining in the area.

The first recorded mention of Gibside goes back to the 13th Century as one of the many properties of the Prince Bishop of Durham (the answer to the question posed at the start). In 1600, the Blakiston family bought the land. William Blakiston built the original and once grand Gibside Hall, the core of which was Jacobean, around 1603 and may have built it on an even older building, as some of the oak floor timbers suggest they date to the 1470s.

It was during the era of the English Civil War that Gibside first became noteworthy. However, the estate rose to prominence when it passed to Elizabeth Blakiston and her husband, Sir William Bowes, a landowner in his own right and an MP, in 1694. The Bowes family, with their long history in the Northeast of England, were already significant landowners and figures in local politics. The marriage between William and Elizabeth further solidified the Bowes family's influence and wealth. George, the son of Elizabeth and William, ultimately became the architect of the Gibside estate we see today.

Following his inheritance in 1722 of the Bowes estates, George went on to amass an enormous fortune from his coal mines and shrewd business acumen. The increasing demand for coal that lay beneath the rural landscape of northeast England brought about a significant transformation both in the landscape and in the fortunes of the landowners. During George’s lifetime, northeast England was at the heart of Britain's coal production, and the Bowes family's estates included extensive coal reserves. Their coal mines became among the most productive in Britain, with George introducing more efficient mining methods and transportation systems, such as waggonways, which allowed the movement of coal more easily from the pits to the River Tyne for shipment to London and other markets, as I wrote of in my piece Of Keelmen.

This infrastructure development significantly increased the output and profitability of George's coal operations. It also helped that in the mid-1720s, George co-founded the Grand Alliance of Coal Owners, a cartel set up to fix prices and maximise profits from the London coal trade. His wealth then enabled him to invest heavily in beautifying and expanding his estates, particularly Gibside, which he began to transform. His vision was to create a grand landscape and stately home that would highlight the power, influence, wealth and aristocratic status of the Bowes family.

George was not just a shrewd businessman. His active participation in local and national politics, which led to his knighthood, played a pivotal role in advancing his interests and the economic prosperity of northeast England. His tenure as a Member of Parliament for County Durham from 1727 to 1760 was a platform to champion the region's interests, particularly in coal and land management, further solidifying his wealth and status. Bowes' alignment with the dominant Whig Party and his political views, shaped by the interests of the landed gentry and industrialists of his time, left an indelible mark on the area.

However, most people in the northeast of England remember George Bowes not for coal or as an MP but for transforming the Gibside estate. It held a special place in his heart, and he looked to create a landscape that reflected his wealth, taste, and social standing in an elegant landscape garden typical of the Georgian era's "naturalistic" style, representing a fusion of architectural brilliance and natural beauty.

While the estate is known for its grand Palladian-style buildings, extensive parklands, and carefully curated gardens, the centrepiece of George's transformation was the construction of the Gibside Chapel, built in the neo-classical style. The first intent of the Chapel, with its domed roof and impressive facade, was to be a private place of worship for the Bowes family, reflecting their aspirations in both expressing their religious faith and enhancing the aesthetic grandeur of the estate. The structure stands at the end of a long, tree-lined avenue, creating a dramatic and picturesque setting. It is still one of the most well-preserved structures in Gibside today.

George also laid out formal gardens, expansive parkland, and other architectural features, emphasising the estate's grandeur. These included the Banqueting House and the Column to Liberty. This towering monument, which predates New York's Statue of Liberty by over a Century, is 140 feet (circa forty-five metres) high. At the top, a female figure – once gilded – standing for Liberty holds the Staff of Maintenance and Cap of Liberty, symbolising the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and justice - a proclamation of George Bowes' political support of the Whig Party. Once visible for miles through the Derwent and Tyne valleys, the Column is still visible from many points on the estate, providing a striking focal point in the landscape.

George built a Gothic-style' Banqueting House' as a Folly with one 'Great' room and two anterooms. Its interior decoration was as elaborate as the exterior, with ceiling and walls covered with an intricate papier mâché design. A 19th-century description records it had mirrors at either end of the Great Room so that "the company when seated appears almost endless in length." It's reported that the family and their guests would use it for picnic meals while touring the grounds.

Those extensive grounds were designed for both beauty and purpose and included a variety of landscapes, from formal gardens to wilder, wooded areas. You can see the Georgian landscape garden style, influenced by contemporary landscape designers such as Charles Bridgeman and Lancelot 'Capability' Brown, in how Gibside's grounds harmonise with the surrounding natural environment. Creating these gardens was a meticulous process involving planting specific trees and shaping the land to create the desired effect. A large walled garden was once used to grow fruit and vegetables for the estate, and now an orchard further illustrates the practical aspects of estate life during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The history of Gibside took a dramatic turn with the life of Mary Eleanor Bowes, George's daughter. He married twice. His first wife, Eleanor Verney, died young, and his second marriage to Mary Gilbert produced their only child, Mary Eleanor. She would inherit his vast estates and fortune, becoming one of the wealthiest women in England. Her life is marked by her significant role in Gibside's history. However, her tumultuous personal life often overshadowed her contributions to the estate.

Mary Eleanor continued her father's work on Gibside, further developing the gardens and adding new features, a notable contribution being the Orangery built between 1772-74. She also commissioned plant collector William Paterson to explore South Africa for rare and new species. The Orangery would have been home to this brilliant, diverse collection of unusual plants. Now a ruin, the original layout of this ample space was into three rooms to the north, known as 'garden rooms'. There was also one large room to the south, purely to display plants. The large southwest-facing windows provided vast light, and a heating system would have kept exotic plants warm during the winter. Evidence suggests that Mary Eleanor used the northeast room as a writing room, and it's likely that, given her social status, she would have entertained guests here.

As one of the wealthiest heiresses in Britain, Mary Eleanor's first marriage was to John Lyon, 9th Earl of Strathmore, thus intertwining the histories of two powerful families, bringing her into the Scottish aristocracy and establishing the Bowes-Lyon family. This lineage would later produce Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, Queen Elizabeth II, and King Charles III. The Queen Mother, whose father (Mary Eleanor's great, great grandson) was the 14th Earl of Strathmore, always enjoyed time spent at Gibside as a child. After the death of John Lyon, Mary Eleanor married Andrew Robinson Stoney, a notorious fortune hunter who subjected her to abuse and tried to control her vast wealth. The couple's separation and later legal battles were widely publicised and scandalous, culminating in divorce, one of the first such cases in Britain of the 18th Century. This period in Gibside's history reflects not only the personal drama of the Bowes family but also broader societal changes, such as shifts in women's rights and legal reforms during the 18th and 19th centuries. Mary Eleanor became known as the "Unhappy Countess"; however, despite her personal struggles, her resilience shone through as she kept her connection to Gibside, and the estate remained central to the Bowes family's legacy throughout the 19th Century.

The Bowes name lives on today through Mary Eleanor's grandson, John Bowes, who founded the Bowes Museum in 1811, a Grade I-listed French-style château in the picturesque market town of Barnard Castle. The museum, which houses paintings by El Greco and Goya – the only works by these artists outside the national collections in London and Edinburgh, is a testament to the Bowes family's cultural and artistic contributions. The belief is that among the other treasures in the museum is a botanical cabinet commissioned by Mary Eleanor to house her exotic plant collections, and this further connects the museum to the Bowes family's history and interests.

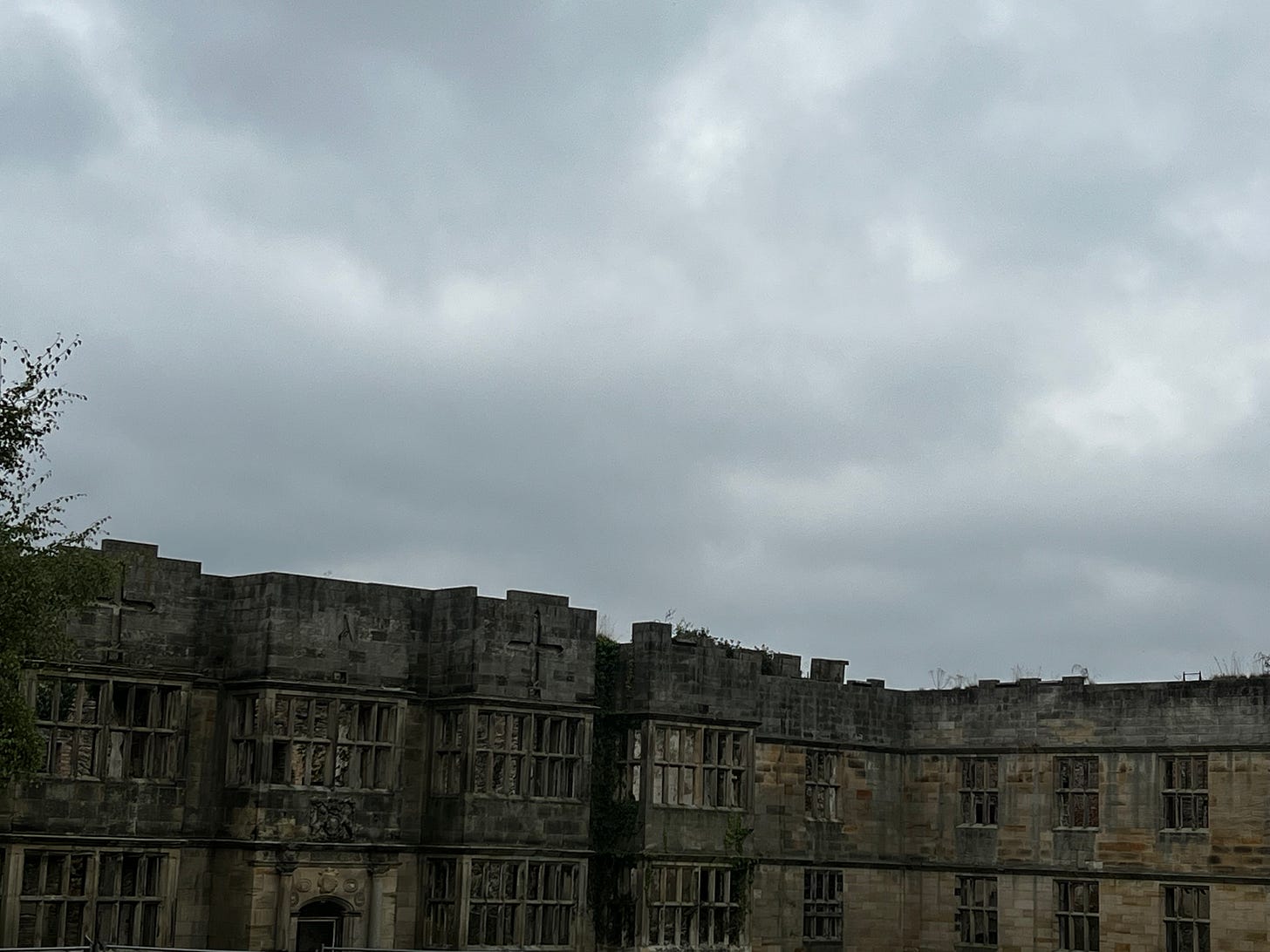

In Mary Eleanor's lifetime, Gibside Hall had three storeys. The decade after her death, a high battlemented parapet replaced the third floor. But Gibside's fortunes declined in the 19th Century, parallel to the waning fortunes of the Bowes-Lyon family, and the estate fell into neglect. With the coal mines exhausted, the upkeep of the grand house and its grounds became financially unsustainable.

The Hall ceased to be a family home in the 1870s, and the Bowes-Lyon family gave up the property in the 1920s (it had provided accommodation to Land Army girls during the First World War). After that, the interiors were extensively stripped out, and the building fell into ruin, with much of the estate becoming overgrown.

When the National Trust took over Gibside in 1965, it embarked on a mission to restore and preserve the estate. The Trust has since undertaken significant work to conserve Gibside's historic buildings, gardens, and landscapes, safeguarding its heritage for future generations. This ongoing restoration work demonstrates the National Trust's dedication to the estate's future. Today, visitors can explore the remaining structures, stroll through the gardens, and enjoy panoramic views of the surrounding countryside. The careful restoration and the estate's natural beauty and diverse wildlife make Gibside a tranquil retreat and a gateway to England's aristocratic past. The National Trust also hosts various events and activities at Gibside, from guided tours that delve into the estate's history to seasonal events like Christmas markets and outdoor theatre performances.

Gibside is not just a historical estate but a living, breathing testament to England's past and future. It is a place where environmental conservation and heritage preservation coexist. From its association with the influential Bowes family to its breathtaking architectural landmarks, Gibside embodies the grandeur and complexity of the Georgian era. Yet, it is also a sanctuary for diverse wildlife, including birds of prey, deer, and rare plant species. The National Trust is committed to enhancing biodiversity at Gibside through various projects, such as rewilding initiatives and native species planting. Visiting Gibside in northeast England offers a unique and fascinating opportunity to appreciate the intricate relationships between history, architecture, landscape, and wildlife.

I took one of the estate's networks of self-guided walking trails on my visit. I chose the Literary Trail, seeking an opportunity to stroll amongst the gardens and wooded areas and discover some hidden architecture. Despite a map and clear signage of the route to follow, I wandered from the path. Once I realised what I had done, I didn't worry. It's not the first time it's happened to me, and it brought back other accidental meanders. In the true spirit of a Flâneur, and as in the song sung by Bonnie Tyler, I've been lost in France and, in my case, many, many other countries, towns and cities. Then again, you discover some little-seen places that way - the local bar of the Venetian Gondoliers, for instance (you'd never believe how tough they think life is for them). On the other hand, the Quartieri Spagnoli of Naples after dark was somewhat more disturbing, but my ultimate shame comes from just before last Christmas.

Sarah and I enjoyed an excellent contemporary Indian Meal in Masala Zone off London's Piccadilly Circus (the brasserie-style restaurant owned by the same company that runs the marvellous fine dining Veeraswamy (London's oldest Indian restaurant) on Regents Street, a short stroll away). Afterwards, Sarah thought we should see the Christmas lights in London's Covent Garden. Full of confidence in my London ‘Knowledge' after forty-plus years of living in and around the city, I suggested we walk. Well, we strolled down plenty of attractive London streets that day, but I never did find those lights ….

Another great account Harry! As my folks still live in Rowlands Gill we walk the dog in Gibside quite often. If anyone wants a ‘reet good read’ about the history of the previous residents of Gibside and indeed the wider Derwent Valley, I can recommend ‘The Dark Side of The Dale’ by Tony Kearney (On Amazon but also https://biblio.co.uk/book/dark-side-dale-grim-gruesome-grisly/d/731144846) If I ever do get on Mastermind I think I’d use this as one of my specialist subject sources!

This is a brilliant and very impressive article, Harry. I've been a volunteer at Gibside for nigh on 18 years and, as you rightly say, the estate is a living, breathing testament to England's past and future. Do you know of the origin of the name "Gibside" ?