To draw no envy, Shakespeare, on thy name,

Am I thus ample to thy book and fame;

While I confess thy writings to be such

As neither man nor muse can praise too much…

The opening lines of Ben Jonson’s poem ‘To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare’

It seems apt that I share this on April 23rd, given that most people consider this to be the day William Shakespeare was born, although no one can be certain, as the record only indicates his baptism on April 26, 1564. Of course, April 23rd was also the day of his death in 1616.

I mentioned in a Substack Note a couple of weeks ago that I was in Durham, in northeast England, on my way to an exhibition of the restored copy of Durham University's Shakespeare First Folio. And I'm not about to embark on some debate as to the Shakespeare authorship question. It may be a fascinating literary mystery, but I'm with the mainstream scholars who feel that a certain William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the thirty-eight plays, one hundred and fifty-four sonnets, as well as the other poems attributed to him. However, I respect those who question whether a man of supposedly modest Grammar school education (that would still include learning Latin and some Greek) and middle-class background could have written such profound, wide-ranging works. And I accept there are no surviving manuscripts in his hand (although scholars believe that might be true of some pages of a manuscript of the play ‘Thomas Moore’). Documents bearing Shakespeare’s signature are more related to financial or legal matters.

Despite the discussion about Shakespeare's authorship of the plays in the First Folio, its publishers, John Heminges and Henry Condell, who were fellow actors in Shakespeare's company, attribute the plays to him and include praise from contemporaries like Ben Jonson. Moreover, no contemporary seems to dispute Shakespeare’s authorship. There is also little doubt of Shakespeare’s involvement in the theatrical industry as an actor, shareholder and playwright, as evidenced by documented records.

In truth, Shakespeare was more of a master adapter than an inventor of original plots, as he borrowed freely from classical sources, contemporary histories, foreign novellas, and older plays. Reliance on such source material was a widespread practice of the time. He likely developed his practice of absorbing and imitating other texts during his time in grammar school, as well as through exposure to classic works translated into English. At least thirty of Shakespeare's plays are based on stories from others, as well as historical accounts, legends, and earlier plays. It is believed that only six or possibly eight plays are largely original or lack a sole source, and even these works draw upon broader literary traditions and familiar themes.

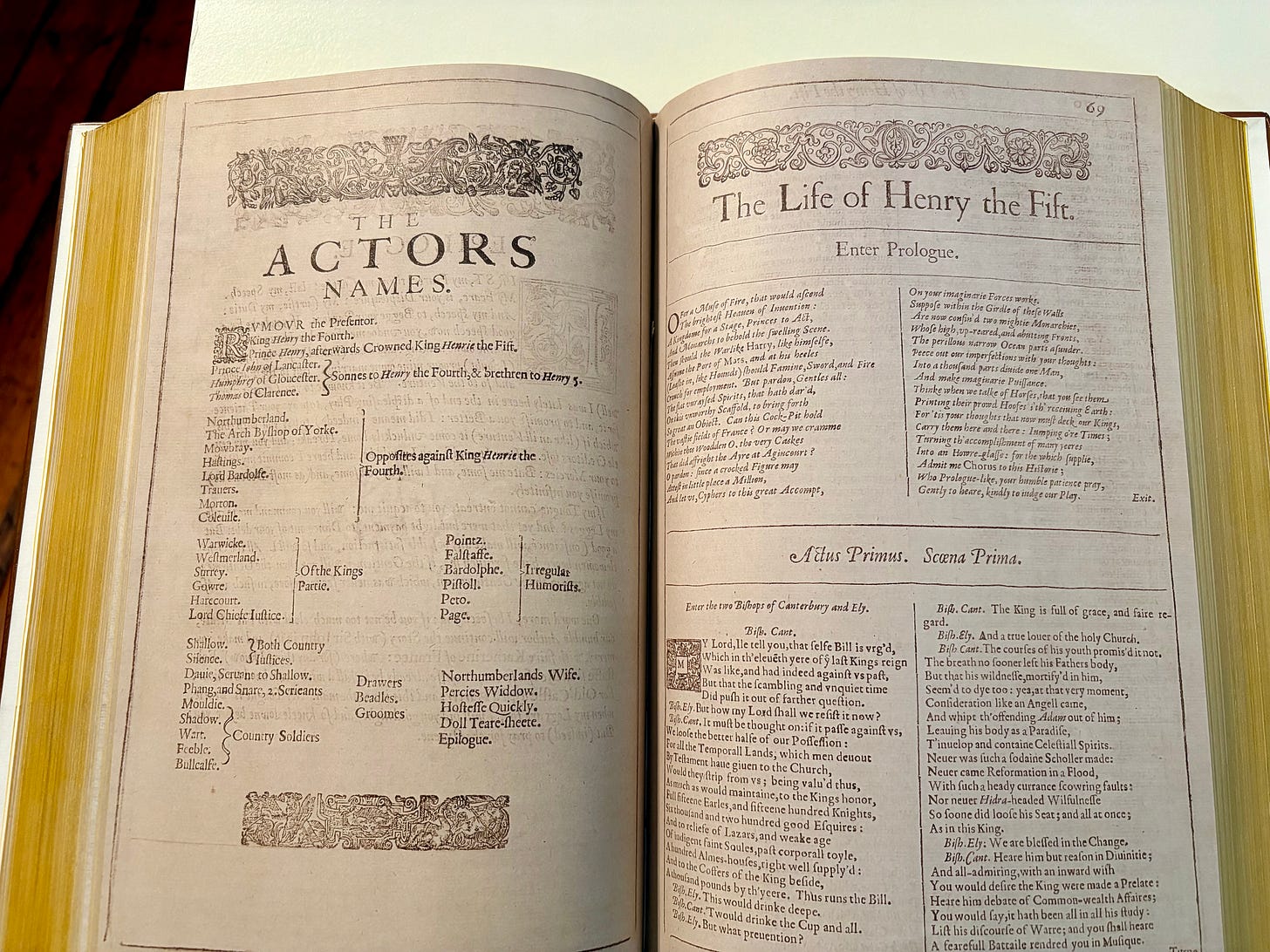

Shakespeare's adaptations of existing stories not only reflect his literary prowess but also serve as a bridge that connects us to a rich literary tradition. Among his plays, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, Pericles, Timon of Athens, and Titus Andronicus all incorporate classical references from the works of authors such as Plutarch. The 'History' plays draw richly from Raphael Holinshed’s ‘Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland’ while Edward Hall's ‘The Union of the two noble and illustrate famelies of Lancastre and York’ was one of Shakespeare's sources for his Henry VI plays, as Hall’s book recalls the history of the Wars of the Roses, into which England descends fully by The Third Part of King Henry VI.

For those plays set outside Britain, Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron is the source for All's Well That Ends Well, while Much Ado About Nothing derives from Matteo Bandello's tales. Additionally, Arthur Brooke's poem The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet served as a key source for Romeo and Juliet, and Giovanni Fiorentino’s Il Pecorone was the primary source for The Merchant of Venice. It's not just the stories of others. King Lear's plot is based on the legend of Leir of Britain, and Shakespeare borrowed elements from the earlier play King Leir, which ends happily; however, Shakespeare transforms the optimistic narrative into a tragedy. While some believe the lost play Ur-Hamlet, possibly by Thomas Kyd, is a precursor to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, others argue that Ur-Hamlet represents an early version of the play that became Hamlet.

Of course, Shakespeare then added his literary magic to his adaptations. He deepened characters like Hamlet, adding emotional and psychological layers, such as Macbeth's guilt. In Othello, which is based on ‘Un Capitano Moro’ by Giovanni Battista Giraldi Cinthio, Shakespeare tightens the plot and adds psychological depth. As I mentioned, he altered endings and, of course, he elevated theme, language, and complexity, turning simple tales into enduring masterpieces. His Romeo and Juliet is shorter, modified for drama, and includes more lyrical elements than the narrative poem ‘The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet’ by Arthur Brooke, which Shakespeare used as a source. He also incorporated supernatural and autobiographical elements into The Tempest, which draws inspiration from the real-life story of the wreck of the ship Sea Venture off Bermuda. In summary, although Shakespeare borrowed from many, his talent transformed the original into a timeless classic.

It's often said that Shakespeare created approximately 1,700 ‘new’ words. Of course, no one can claim that he was the first to use them, but it was his work that survived in writing, which is why we believe he coined them. Still, he was wildly inventive, especially with ‘noun-ing’ verbs (e.g. taking grace and creating to grace) and the reverse of ‘verb-ing’ nouns (e.g. amazement from amaze). He also created compounds (e.g. barefaced, eyeball, bedroom) and played with prefixes/suffixes (e.g. dishearten, uncomfortable, dauntless, eventful)

And one might argue that Shakespeare's expressions have had a more significant influence on the English language than his creation of individual words. Phrases like 'Break the ice,' 'Heart of gold,' 'Bated breath,' 'Wild-goose chase,' and many others have certainly stood the test of time and are still commonly used.

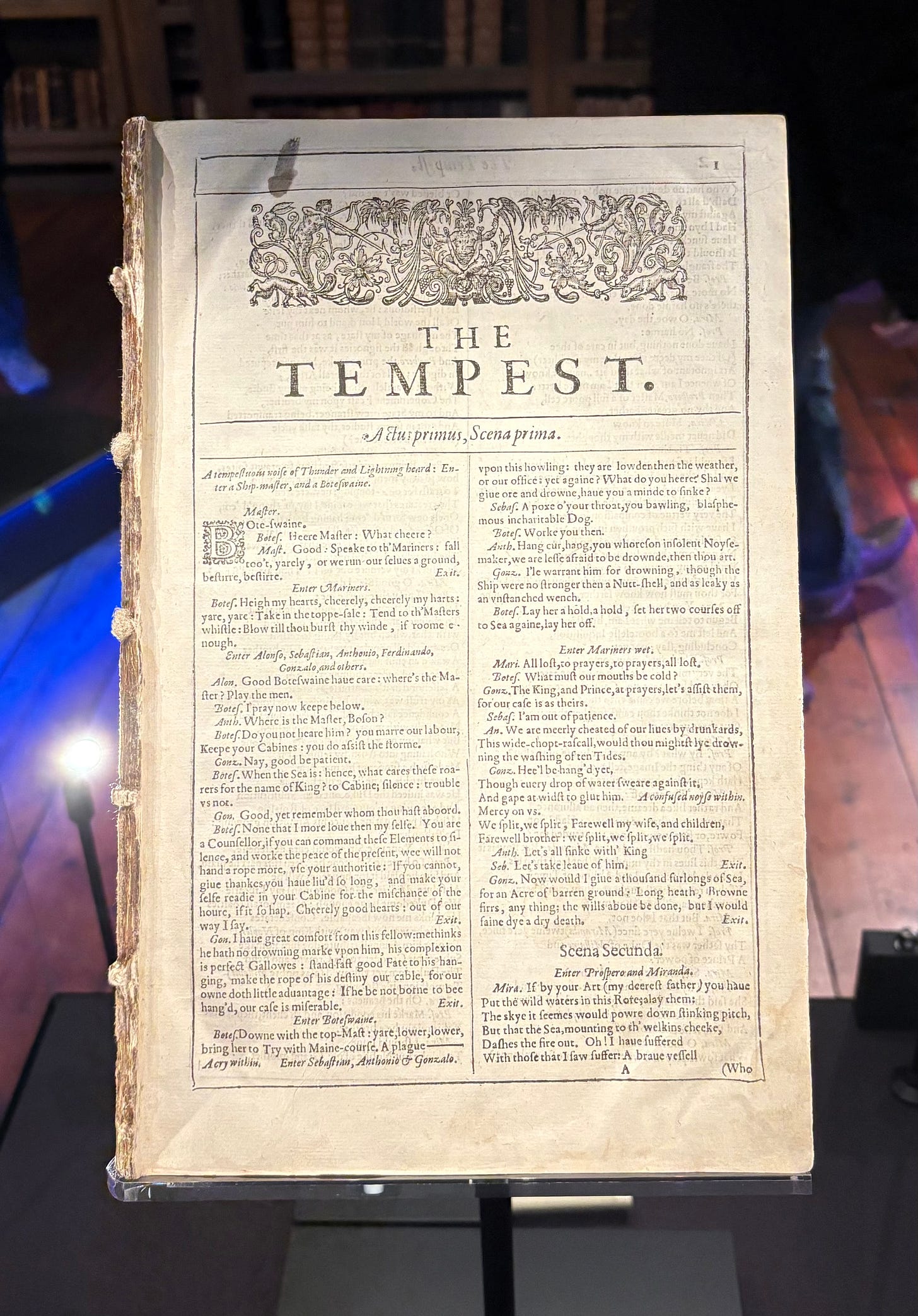

Anyway, enough of the man’s writings, let's examine one of the most important and influential books in English literature: the first collected edition of William Shakespeare's plays, published in 1623, seven years after his death. Commonly referred to as the First Folio, its official title is 'Mr William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies.' This book not only preserved Shakespeare's works but also made a significant contribution to his literary legacy.

The term "folio” refers to the book’s format, in which four pages of text are printed on two sides of a sheet. Each sheet is then folded once to form two leaves. The use of this format signifies that the plays are considered substantive and dignified rather than merely ephemeral entertainment.

While the First Folio is a marvel of early printing, it also bears charming and revealing quirks. As a hand-composed, manually printed book produced by a team of compositors and printers using relatively primitive technology, it is not surprising that it displays numerous inconsistencies and idiosyncrasies. The use of 'long s' that resembles an 'f' to modern readers, ligatures (like 'ct' or 'ſt'), and blackletter headings were standard. There is also inconsistent use of italics for stage directions or character names.

The reason for the glitches is that different compositors worked on various parts of the book. Each compositor had distinct habits, spelling styles, and levels of accuracy. Some were careful; others made errors or inserted punctuation with dramatic pauses, commas, and colons appearing arbitrarily due to compositor style rather than authorial intent. Spelling is also inconsistent (e.g. doe vs do, show and shew) even within a single play and sometimes on the same page.

Other errors include missing words, repeated lines, or jumbled phrases. Some copies of the First Folio display 'stop-press' corrections, where the printer noticed an error partway through the printing process and corrected it in subsequent sheets. This means not all First Folios are precisely the same.

However, despite these glitches, the First Folio is significant not only because it cemented Shakespeare as a literary genius but also because, without it, we would not know about eleven of his plays. Some classics, too, including Macbeth, Julius Caesar, Twelfth Night, The Tempest, and As You Like It. Unlike earlier, less accurate 'quarto' editions, the First Folio is the most reliable source for many Shakespeare plays. For instance, in the First Folio, Hamlet's famous "to be or not to be" soliloquy appears with significantly different wording and punctuation than in earlier quarto editions. The Folio version adds clarity and drama, with punctuation shaping how it's read and performed.

But why First Folio? Well, because there are three more. The production of the First Folio, including Ben Jonson's famous tribute, was to honour Shakespeare's legacy and preserve and standardise his plays. The Second Folio, produced about nine years later, cemented the structure and sequencing of the plays, corrected minor spelling changes, and featured typographic updates. More significantly, it included new dedicatory poems, such as John Milton's first published poem.

The third Folio, produced nearly fifty years after Shakespeare's death, presents a problem because it introduced controversy by broadening Shakespeare's canon without solid textual evidence. It contains seven 'apocryphal plays,' with all but one written by different authors. The consensus is that Shakespeare contributed to one of these, Pericles, likely in collaboration with George Wilkins as a co-writer. The other apocryphal plays, written by others, include Locrine, The London Prodigal, Thomas Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle, The Puritan (or The Puritan Widow), and A Yorkshire Tragedy. These were all added to trade on Shakespeare's name and boost sales. Despite the flaws in the third Folio, it is a rare edition because the Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed most copies, making those that survived uncommon.

What made such misattribution easier was that collaboration was widespread in Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre. Shakespeare was no stranger to this collaborative world. Based on scholarly consensus and modern attribution techniques, it is widely believed that ten of Shakespeare's plays may have been co-written. I've already mentioned Pericles, and there is evidence that Macbeth and Measure for Measure were co-written with Thomas Middleton, while Titus Andronicus was possibly co-written with George Peel.

The publication of the fourth and final Folio occurred in 1685 and was intended for an expanding reading audience. It featured more editorial changes, including shifts in punctuation and spelling, and ultimately served as the primary source text (although it is further from the 'accuracy' of the First Folio) for many 18th-century editions of Shakespeare’s plays, including those by editors such as Nicholas Rowe and Alexander Pope.

About 750 copies of the First Folio were printed, of which 235 are known to have survived. The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., holds the most extensive collection, with eighty-two copies. Libraries and museums worldwide, including the British Library and the Bodleian Library in the UK, as well as the Cosin Library at Durham University, which I visited, house other copies.

Bishop John Cosin likely acquired his First Folio around its publication date in 1623, adding it to an already noteworthy literary collection. His library, established in 1669 on Palace Green in Durham, is just a stone's throw from the magnificent cathedral and reflects Cosin's dedication to education and culture. Indeed, it was one of the earliest ‘public’ libraries in northern England, with Cosin intending for it to serve clergy and local scholars, thereby making learning more accessible. A radical idea for the time.

The library is predominantly constructed from local sandstone, giving the structure a durable and regionally relevant aesthetic. The building’s exterior design is a remarkable example of 17th-century English architecture, blending classical symmetry with ecclesiastical dignity. While rooted in the English Baroque style, it has a harmonious, symmetrical façade typical of post-Renaissance ideals of balance and proportion, reflecting the bishop's European travels and intellectual outlook.

Inside, the library features a long, rectangular hall with large sash windows on both sides, providing the natural light necessary for reading in the 17th century. There is a lot of rich wooden panelling and custom-built bookcases, often integrated into the architecture itself, which is a hallmark of libraries of this period. A raised gallery lines part of the room, providing additional storage and visual grandeur, while a barrel-vaulted ceiling adds height and drama.

Those who have read my Luxmuralis will realise Bishop Cosin was no ordinary Bishop. He was a Prince Bishop, the supreme ruler of northeast England, endowed with powers delegated by the British monarch, which granted a Prince Bishop secular power and religious authority to raise both armies and souls. Cosin staunchly supported High Anglicanism, favouring ceremony, liturgy, and church hierarchy. After the English Civil War, he spent several years in exile in France because of his Royalist sympathies. Following Charles II's Restoration, Cousin returned to England and was appointed Bishop of Durham, helping to restore the Church of England’s structure. He wrote works that defended Anglican liturgy and practices and contributed to the revisions of the Book of Common Prayer. His writings always emphasise church tradition, scripture, and rational faith as foundational to Anglican theology.

Cosin's Library ultimately encompassed about 5,000 titles, reflecting a wide array of subjects and interests, particularly rich in theology, liturgy, and canon law. A notable item is the 1619 Book of Common Prayer, annotated with Cosin's insights for the 1662 revision, offering a window into the evolution of Anglican liturgical practices. The library also houses significant medieval manuscripts, including a 12th-century history of Durham Cathedral by Symeon of Durham, providing invaluable insights into the region's ecclesiastical history. Additionally, the collection features a first edition of Thomas More's Utopia, exemplifying Renaissance humanist thought. During his exile in France, Cosin acquired numerous French Protestant works, many of which were printed in provincial towns. These works include rare pamphlets not even found in the Bibliothèque Nationale, the national library of France in Paris and reflect the religious controversies of the 16th and 17th centuries. All the books in the library are exquisitely bound except for one.

And which book is that? Well, it’s the Durham copy of Shakespeare's First Folio, the only known First Folio that has remained within the same personal collection (excluding a ten-year enforced gap) since its initial purchase.

In December 1998, after centuries of use by scholars for research, perpetrator(s) in broad daylight forced open display cases from an exhibition at the library and took Durham's First Folio, six other rare books, and some manuscripts. Among them were an English translation of the New Testament, a first edition of Beowulf, and a fragment of a poem by Geoffrey Chaucer.

The location of the First Folio remained unknown for ten years, and the book was feared to be lost. Then, in 2008, a man presented a damaged First Folio, which he referred to as "an old Shakespeare book," claiming to have found it in Cuba. He provided his name as Raymond Scott, stating that he was a businessman from northeast England. He agreed to leave the book with the Folger Library to gain authentication. The book had suffered considerable damage with its binding and title page removed to conceal its origin, but experts at the Folger soon identified it as the stolen Durham copy.

After the book’s verification, the police took action, and investigations revealed that Raymond Scott, who was an unemployed ‘antique dealer’ and heavily in debt, lived in the small town of Wingate, situated less than ten miles from Durham. Two years after Scott delivered the Durham Folio to the Folger, it was returned to Durham, and Scott was found guilty of handling stolen property. Although acquitted of theft charges, he still received an eight-year prison sentence. Scott claimed in an interview after the trial that he was indeed the thief, and tragically, two years into his sentence, he committed suicide.

Upon its return, Durham University's conservation team undertook extensive efforts to stabilise and preserve the First Folio. The damage had left the book vulnerable, necessitating careful restoration to ensure its longevity and accessibility for future study.

You can now see the result of that painstaking work in 'Shakespeare Recovered: Durham's First Folio' at Cosin’s Palace Green Library. This exhibition not only highlights the enduring significance of the First Folio in the literary world but also recounts the recent tumultuous journey of Durham's copy and the delicate conservation work undertaken to restore it. It's worth a visit if you happen to be near the city.

Pivoting about St. George's (Apr 23)

Thanks Harry for this piece, it's encouraged me and redirected me to read the Bard's work before I shuck this mortal coil. Your depth of knowledge is fascinating to me and I leave your readings uplifted and encouraged, refreshed. Bill and I share the same birthday.