"Trincomalee is a wonderful elder lady of the sea who certainly has some tales to tell of life on the high seas. She is a very prominent and iconic landmark in Hartlepool whom the people of the area and indeed the region have taken to their hearts."

David McKnight - General Manager of HMS Trincomalee

Earlier this year, I wrote about visiting Hartlepool to see the John Bulmer photography exhibition in John Bulmer - Northern Light. As I was leaving the exhibition, I noticed the tops of some sailing ship's masts in the distance above the rooftops. I then discovered the masts were those of HMS Trincomalee, so I recently returned to the town to discover more about the ship and her home within Hartlepool's Royal Navy Museum.

The museum is part of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, which has multiple sites across the UK, each offering a distinct perspective on British naval history. My visit provided an engaging glimpse into the history of the Royal Navy and naval life in the 18th and 19th centuries. A journey back in time and a discovery of shipbuilding, maritime warfare, and the lives of sailors of that era.

Stepping through the museum's doors instantly transports you to a Georgian quayside frozen in time. The meticulously recreated 18th-century buildings, bustling with 'life' aided by models and sound effects, offer an immersive experience of an English coastal town during that era. Volunteers, dressed in period costumes, further bring the historical environment to life by reenacting the era's naval activities, trades, and everyday life.

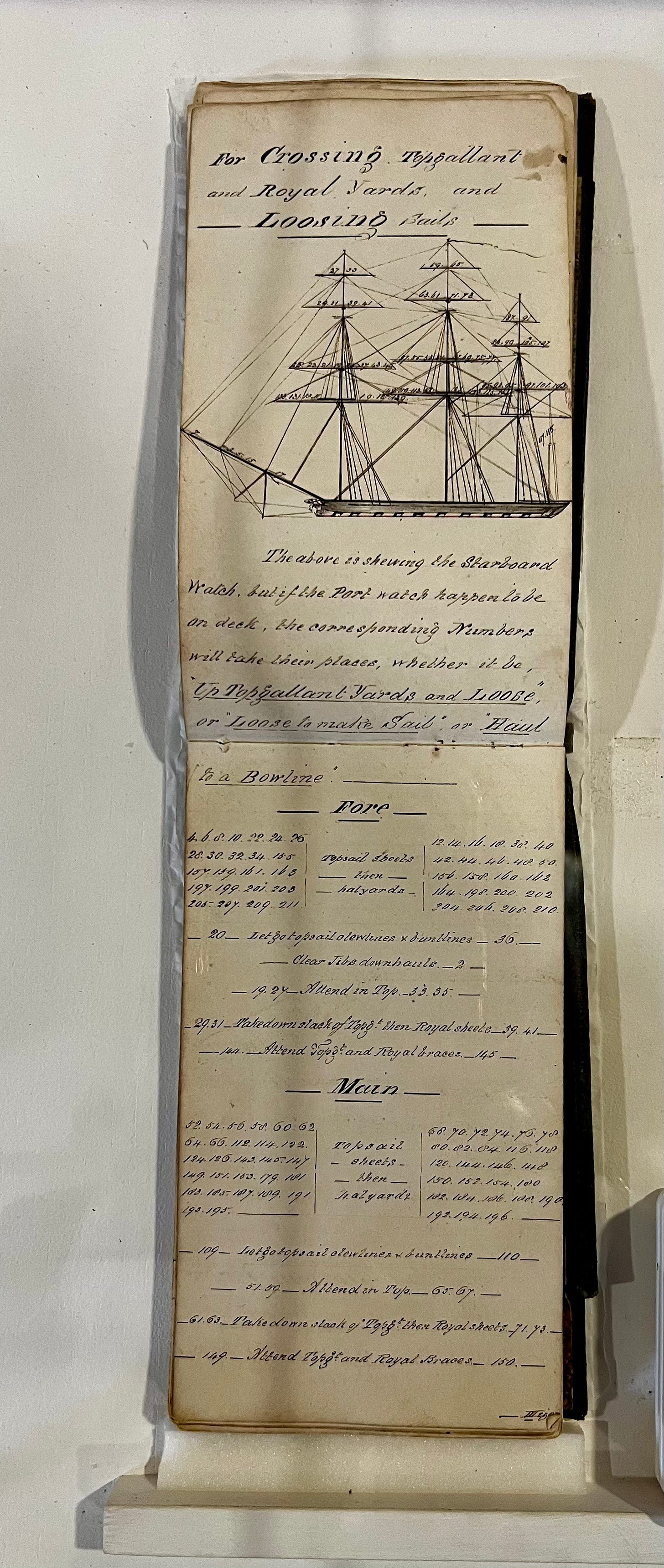

The museum's static displays are a treasure trove of knowledge on shipbuilding, naval technology, and the experiences of sailors and officers during the 18th and 19th centuries. The displays also feature many artefacts, including naval weapons, uniforms, and sailors' personal items. The museum's educational programmes, designed for school groups, offer a variety of activities and workshops. These programmes provide hands-on experiences and insights into the daily life of sailors, naval tactics, and ship construction. For example, there are workshops on knot tying, navigation, and even a 'day in the life of a sailor' simulation.

But the sight of HMS Trincomalee, the museum's jewel-in-the-crown, steals the show. This Leda-class frigate of the Royal Navy, launched in 1817, is one of the oldest warships still afloat today. The ship derives its name from the Battle of Trincomalee, fought in 1782, an indecisive naval engagement between the French and British during the American War of Independence.

The size of a ship like Trincomalee would typically require timber from over 1,000 oak trees. However, the shortage of European oak in the early 19th century caused steep price rises in Britain and resulted in the outsourcing of shipbuilding to various British Empire colonies. Trincomalee was, therefore, built from Malabar teak wood in what is now Mumbai in India, a sign of the global nature of English naval shipbuilding in the 19th Century.

Jamsetjee Bomanjee Wadia, a prominent Indian shipbuilder and member of the Wadia family, built the Trincomalee. During British colonial rule, the Wadia family pioneered maritime trade and ship construction, transforming Mumbai into a critical centre for shipbuilding and commerce. The Wadias built merchant ships and warships for the British East India Company and the Royal Navy during the 18th and 19th centuries, making the Mumbai shipyard one of the most important in the British Empire.

Jamsetjee Bomanjee Wadia was among the first Parsi shipbuilders to gain international recognition for his shipbuilding skills. His work exemplified the cross-cultural exchange of the time, applying Indian artisanry to British naval design and strategy. Jamsetjee was a master shipbuilder at the Mumbai shipyard, renowned for constructing high-quality ships. His artisanry and ability earned him a powerful reputation in the shipbuilding world, and the vessels built under his leadership were recognised for their strength and durability.

As a complete aside (these pieces are 'meanders', remember), the poem that became 'The Star-Spangled Banner', America's national anthem, was written on a ship built by Jamshedji Bomanjee Wadia—the HMS Minden, the first ship commissioned by the British Royal Navy from India.

In 1814, Francis Scott Key, a Baltimore author and lawyer, wrote a poem in captivity aboard the Minden after the British bombarded American forces at Fort McHenry in the Battle of Baltimore overnight on September 13, 14. When daylight broke, through the smoke, Key could see the American flag still fluttering from the fort, which inspired him to write the poem 'In Defence of Fort McHenry', which was adopted as the American national anthem, 'The Star-Spangled Banner', in 1931.

Jamsetjee's descendants continued to build ships well into the 19th and 20th centuries, a testament to their pivotal role in connecting Indian artisanry with British naval power. Although the Wadia Group is no longer in shipbuilding, it remains a vital part of India's business landscape, serving as a living link to the Parsi community's crucial role in trade, industry, and entrepreneurship in India.

Returning to Trincomalee, it's helpful to understand what a frigate was in the context of the 18th and 19th centuries. The British Royal Navy employed a rating system to classify warships based on their size, armament, and crew. While not a precise science, this system primarily focused on the number of cannons a ship carried, which determined its role and status within the fleet. Warships were categorised into six rates, with larger powerful ships ('Ships of the Line') receiving higher ratings and smaller, more agile vessels falling under lower ratings.

A first-rate Ship, such as HMS Victory, typically carried between 100 to 120 cannons over three gun decks with a crew of about 850 to 1,000 men. These were the largest and most powerful warships, designed to fight in the line of battle in significant engagements. Second-rate ships typically carried between 90 and 100 cannons on two or three gundecks with a crew of around 750 men. These ships also took part in the line of battle. Called upon when first-rate ships were unavailable or in support of first-rate ships in large naval engagements. The most well-known second-rate ship is the 'Fighting' Temeraire, which I wrote about in Turner - Art, Industry, Nostalgia. The most common configuration of third-rate ships was seventy-four guns over two gun decks and a crew of between 500 and 650 men. These ships, such as HMS Bellerophon, took part in many critical battles during the Napoleonic Wars, including the Battle of Trafalgar. They were the fleet's workhorses, valued for their combination of firepower and manoeuvrability. There were more ships with this rating than any other ships of the line. In addition to fleet action, they played a vital role in blockades. I mentioned HMS Minden earlier, and this, too, was of the third rate. Fourth-Rate Ships carried 50 to 60 cannons on one or two gun decks, manned by 350 to 400 men. These ships sometimes took part in the line of battle, especially in the early 18th century. But by the 19th century, the main use of fourth-rates was on duties that needed less 'firepower' such as escort duties, patrolling, or 'policing' in distant colonies. The design of Trincomalee was as a fifth-rated ship, one of the forty-seven Leda-class frigates built. She carried 38 cannons and was crewed by 240 men. The Leda class design was based on the French frigate Hébé, which the British captured in 1782. Typically, three square-rigged masts carrying substantial amounts of sail made them fast and agile and thus ideal for surveillance and rapid attack roles. Their strategic importance was not in direct engagement in naval warfare but in their speed and agility, which made them useful for scouting ahead of the fleet, engaging in commerce raiding (privateering), protecting convoys, and conducting blockades. Sixth-rate ships, commonly called post ships, carried 20 to 28 cannons on a single gun deck and had around 150 to 200 crew. Their primary use was patrolling, escorting smaller convoys, carrying messages, and engaging in minor combat actions. These were the smallest ships considered suitable for a captain to command, and a fictional example is HMS Surprise, the 28-gun ship depicted in Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series. Other unrated ships that carried fewer than twenty cannons included corvettes, sloops, brigs, cutters, and gunboats for coastal defence, patrol duties, communication, and anti-piracy missions. They often served in shallow waters where larger ships could not navigate. An example of a brig-sloop was the HMS Beagle, which famously carried Charles Darwin on his voyage around the world in his research for his book 'Natural Selection'.

By the mid-19th century, with the rise of steam power and ironclad ships, the traditional rating system became less relevant. The introduction of steam frigates, armoured warships, and more advanced naval technologies transformed ship classification. The Royal Navy eventually moved away from the old rating system as naval warfare evolved. New categories were derived to classify ships by their purpose, such as battleships, cruisers, corvettes and destroyers.

But let's return to these older frigates crucial in supporting Britain's dominance of the seas during the 18th and early 19th centuries, particularly during conflicts like the American Revolutionary War, the Napoleonic Wars, and the War of 1812. These frigates were not just ships but strategic assets, given their ability to operate independently and their firepower, speed, and range. Their smaller crew size compared to larger ships of the line also made them more economical for long-distance voyages for diplomatic missions or exploration, along with their scouting duties.

Even though the Napoleonic wars were over by the time of Trincomalee's launching, other frigates played a crucial role in that war, engaging in blockades of French ports, protecting British trade routes, and intercepting French privateers and smaller warships. Their adaptability was a quality that set them apart. Horatio Nelson, who began his career commanding a frigate, once wrote while pursuing the French fleet in the Mediterranean when he desperately needed knowledge of his opponent: 'A fleet can never have enough frigates. Were I to die at this moment, want of frigates!' would be stamped on my heart.

But the war being over the Trincomalee was one of the last frigates of the Leda class built for the Royal Navy. On completion, she sailed to Portsmouth destined for 'reserve.' For that journey, she travelled with a small crew and a cargo of timber and wounded soldiers and sailors. Also on board was Eliza Bunt, the widow of a Royal Navy boatswain of HMS Victory who had worked at Trincomalee dockyard in Sri Lanka, her two small children and her pet parrot, Poll. Eliza, a woman of remarkable resilience, kept a diary during the five-month voyage, providing a fascinating record of a woman's experience on a Royal Navy ship. Eliza is frank about the discomfort, regular seasickness and various abuses of alcohol by the crew, especially her manservant! However, the ship's officers seem to have generally looked after Eliza well, and she was often a dinner guest of Captain Hill in his cabin. On its journey to England, the ship called into various ports to pick up more invalids and stores, including St Helena. Napoleon's prison island since his defeat at Waterloo in 1815. When the ship spent some time off the island of Mauritius, a former French colony, Eliza remarked: 'I do not like the French manners and am still more sorry to see my own country women pursue the French manners so much as they do.' Neither was Eliza impressed with Ascension Island, which she described as "a dismall place to look at". Overall, Eliza's voyage was not particularly happy, but that might not have been just because of the discomforts of ship life as she was missing a man called Thomas Craven, whom she had left behind in Sri Lanka. He appears to have befriended Eliza and led her to believe he would follow her home to England and that they would marry. Thoughts are that Eliza may have written the diary as a record that Thomas might read in the future. Sadly, he married someone else, and Eliza settled into a single life with her children in Portsmouth.

In reserve, Trincomalee became a 'Ship in Ordinary' with her masts removed and her hull covered by a roof to keep out the rain. There, she stayed for some twenty-five years before receiving her first commission. By then, the naval authorities saw her as outdated, so they converted her to a sixth-rate corvette with twenty-six cannons for her deployment in various regions, including the West Indies, the Pacific, and North America, fulfilling roles ranging from patrol duties to safeguarding trade routes. While Trincomalee did not see any significant naval battles during her service, she did participate in policing British maritime interests, anti-piracy missions, and diplomatic voyages, eventually sailing over 100,000 miles. Her ultimate decommissioning was at the end of her active service in 1857.

After her final decommissioning, HMS Trincomalee was repurposed in 1907 as a Royal Navy training ship and renamed Foudroyant. She continued in that role into the early 20th century, but by the 1980s, after years of neglect, the ship was in poor condition, and her scrapping was on the cards. However, a major restoration project saved her, and in 2001, she was fully restored to her 19th-century appearance, becoming the museum ship, one sees today.

.

Harry, your piece about HMS Trincomalee is a great journey through time. You blend maritime history with personal reflection, making it a really rich and intriguing read.

Loved this piece, Harry! Thank you for bringing us on the journey!