Luxmuralis

Some photographs and some words...

Northumbria in the age of Cuthbert and Bede was the Tibet of the British Isles. In windswept monasteries on rocky headlands, muddy riverbanks and tidal islands, bands of shivering monks would offer up Latin incantations for a good harvest or protection from sea-borne danger.

Dan Jackson - The Northumbrians (North-East England and Its People)

Although I've visited Durham Cathedral a few times since my return to the northeast of England (and countless times in my lifetime), I have written little about it; a week or so back, I was there again for 'Space' by Luxmuralis, a UK-based artistic collective specialising in creating immersive light and sound installations. The collective’s leaders are Peter Walker, an artist and sculptor, and David Harper, a composer and sound artist. Their work aims to evoke in people a sense of awe and contemplation in cultural and religious spaces by blending light, sound, and architecture, encouraging audiences to think about their surroundings in quite literally a different 'light'.

However, before I delve into the mesmerising experience that was 'Space', I want to take a moment to explore Durham Cathedral's history. It's a marvellous building that's a shining example of Norman architecture. Light shows or not, I'd humbly suggest that this UNESCO World Heritage Site is a must-see for anyone visiting the northeast of England.

The cathedral's story begins with the community of St. Cuthbert, affectionately known as 'Cuddy' in northeast England. This community revered Cuthbert as one of the most important saints in early medieval England. And as ever with my Meanders, just as an aside, I will add that confusingly in the northeast dialect, 'Cuddy' also means a small horse, 'Cuddy's Duck' an Eider duck, 'Cuddy's legs' are Herrings and a 'Cuddy Wifter' is a left-handed person. You can see why such unique dialect references often challenge visitors from other parts of England when they visit the northeast.

Anyway, back to Cuthbert, and while little is definitively known about his early life, the belief is he was from the Scottish / English Borders area and possibly born into a noble or relatively affluent family. According to medieval accounts, such as Bede's 'Life of St. Cuthbert', a hagiography that provides a detailed account of Cuthbert's life and miracles, Cuthbert, while working as a shepherd, saw a vision of St. Aidan, the once Bishop of Lindisfarne Monastery, a remote island monastery off the coast of Northumbria, ascending to heaven. Inspired by this experience, Cuthbert committed his life to the service of God and entered Melrose Abbey, a monastery founded by monks from Lindisfarne. His entry into monastic life around 651 marked the beginning of a life dedicated to Christian service.

At Melrose, under the guidance of Abbot Boisil, Cuthbert's discipline, asceticism, and leadership skills shone. His ability to inspire others and his unwavering commitment to the monastic life led to his promotion to the role of Prior. Cuthbert was then the natural choice when the Melrose community needed a leader at Lindisfarne. His wisdom, pragmatism and moderation marked his leadership during a period of religious turbulence for the Christian Church, as the Celtic Christian traditions and practices of Lindisfarne clashed with those of Rome.

Although Cuthbert's early monastic life was within the Celtic Christian traditions, he accepted those of Rome. He worked tirelessly to reconcile the differing Christian traditions while ensuring the spiritual growth of the monastic community. His holiness and dedication to the austere life of prayer, fasting, and service set an example for others. Beyond the monastic walls, Cuthbert's work among Northumbria's rural and often isolated communities inspired many. He travelled widely on foot, preaching to the region's people, converting many to Christianity, and offering pastoral care to the poor and sick. His ability to connect with people on a personal level, along with his humility, kindness, and skill in explaining the gospels, established him as a prominent figure in the spread of Christianity in northern England.

But Cuthbert also sought solitude in his quest for spiritual closeness with God. In 676, he retreated to Inner Farne, a small, isolated island off the Northumbrian coast, where he lived as a hermit for several years. His time on Inner Farne is the subject of many legendary stories about his connection with nature and his miraculous powers (more on those later). Medieval accounts tell of how birds and animals would gather around him and how he could perform healing miracles.

While this period of isolation allowed Cuthbert to live out his ascetic ideals, deepening his relationship with God and intensifying his focus on prayer and meditation, his desire for solitude did not last. Cuthbert's reputation for holiness and leadership saw him elected In 684, albeit against his wishes, as Bishop of Lindisfarne, requiring him to return to more active leadership within the Church. This again came during a time of political and religious importance for Northumbria, and the Church saw Cuthbert as a stabilising figure who could offer guidance again through challenging times.

During his brief episcopacy, Cuthbert focused on pastoral care, serving as a spiritual leader for the clergy and the laity—however, his time as bishop was short. By 687, feeling the call of a more contemplative life again, he retired to Inner Farne, where he soon died.

The monks buried him in a simple grave at Lindisfarne Monastery, and his tomb quickly became a pilgrimage site. Eleven years after his death, the exhumation of his body for its enshrinement supposedly found it incorrupt, a miracle that increased his fame. Once the shrine was built to house his remains, it drew even more pilgrims.

However, in the late 8th century, Viking raids shattered Lindisfarne's peaceful life. In 793, one of the first and most devastating Viking raids on Britain occurred at Lindisfarne, leaving the monastery vulnerable. Although the monks initially managed to protect the remains of St. Cuthbert, the ongoing threat of Viking attacks made it increasingly dangerous for them to stay on the island, so In 875, fearing for the safety of St. Cuthbert's remains, the monks decided to leave Lindisfarne and take his body with them. This marked the beginning of a long and arduous journey.

The monks carried St. Cuthbert's coffin and other relics, including the Lindisfarne Gospels, for over seven years across the northern countryside. Their unyielding belief that St. Cuthbert himself was leading them through divine signs prompted them to pause at various places, such as Norham, Melrose, and Ripon.

After years of wandering, in 883, they came to Chester-Le-Street, a village some ten miles south of Newcastle, a more settled area where they built a church where St. Cuthbert's remains rested in this relatively peaceful location for 112 years. But by the late 10th century, the political landscape of Northumbria had changed, with growing conflicts between Viking raiders and the Angle kingdom.

So in 995, according to legend, the monks moved St. Cuthbert's coffin again, coming upon a place a few miles from Chester-Le-Street called Dun Holm (a merger of Old English dun meaning 'hill' and Scandinavian holmr meaning 'small island in a river'). The coffin suddenly became too heavy to move, and the monks saw this as a divine sign. They believed St. Cuthbert had chosen Dun Holm (that became Durham) as his final resting place. A vision of St. Cuthbert supposedly appeared to one of the monks, instructing him to settle Cuthbert's remains at this naturally defensible site on a rocky peninsula surrounded on three sides by the River Wear.

So, Cuthbert's followers built a church to house the saint's remains. To begin with, it was a simple wooden structure that, like his shrine on Lindisfarne, quickly became a centre of pilgrimage. Cuthbert's community thrived in Durham, and in 1093, following the Norman conquest, the building of the grand cathedral we see today began as a more permanent home for the saint's remains. It took forty years to complete construction, though additions continued in later centuries.

Many now consider the cathedral one of the finest examples of Norman (Romanesque) architecture, famed for its massive walls, large columns, semi-circular arches, and flying buttresses, all hallmarks of Norman design. It also has some of the earliest examples of rib vaulting in Europe, which allowed for higher ceilings and more complex structures that were revolutionary for their time, making the cathedral a model for the Gothic architecture that followed. The late 12th century saw the addition of the Galilee Chapel at the western end of the cathedral.

The cathedral soon became one of the most important pilgrimage sites in medieval England as well as playing a significant role in the power of the Prince Bishops of Durham, influential ecclesiastical figures who, from the late 11th century, ruled over the semi-independent region known as the Palatinate of Durham. The Prince Bishops wielded religious and secular authority with the power to raise armies, mint coins, administer justice, and collect taxes. All powers usually reserved for the king. This exceptional authority was granted due to the strategic importance of Durham in the border region between England and Scotland.

Durham Cathedral's location on a rocky hill almost surrounded by the River Wear made it an ideal defensive structure, complex for attackers to approach. It was part of a fortified complex that included Durham Castle, built by the Normans earlier to suppress northern uprisings and defend England's northern border against Scottish raiders.

Durham Castle's construction began some six years after the Norman Conquest of England. Following the conquest, the newly crowned King William found his attempt to consolidate his control over northern England difficult due to resistance from the Angle nobility with continuous threats of rebellion. William started a brutal campaign known as the 'Harrying of the North' around 1069 to suppress Northumbria, destroying much of the area to quell resistance.

The original Durham Castle was a motte-and-bailey structure, a typical Norman fortification consisting of a central keep (motte) on a raised earthwork and an enclosed courtyard (bailey) surrounded by defensive walls. Over the years, a stone building replaced the wooden structure, turning the castle into a formidable medieval fortress that reflected its importance as a military stronghold, evident in its strategic location and robust design.

In addition to the castle being the residence of the powerful Prince Bishops and a fortress, it was also a centre of administration and governance for the Palatinate of Durham. The Prince Bishops' role was symbolic and practical, as they oversaw the strategic planning and execution of defensive measures and were often called upon to protect the region from Scottish incursions. Symbolising their political and military dominance, each successive bishop left their mark on the castle, with various additions and improvements made over the centuries.

Durham Castle's significance as a defensive structure diminished during the English Civil War, and in 1646, Parliamentarian forces seized the castle after the defeat of the Royalists. The Commonwealth period briefly curtailed the Prince Bishops' temporal powers, but these were restored with the monarchy in 1660 following the Restoration of King Charles II.

The legacy of the Prince Bishops endured into the 19th century, although the English crown gradually stripped away their secular powers. The last Prince Bishop to wield significant political power was William Van Mildert, appointed in 1826. His tenure marked a turning point in the diocese's political authority, leading to its full integration into the governance of England.

In a transformative decision, Van Mildert played a crucial role in setting up Durham University in 1832, the third oldest university in England. The castle was donated to it to become the home of University College, one of its constituent colleges. Since then, Durham Castle has served as a student residence and centre for university events and ceremonies.

Let's return to the cathedral and the 11th century when it was home to a community of Benedictine monks who lived and worked in the attached monastery. The monks, known for their dedication to prayer, work, and hospitality, played a vital role in supporting the cathedral and offering hospitality to pilgrims. While their presence and influence were significant in the cathedral's history and development, sadly, during the English Reformation under King Henry VIII in the 16th century, their monastery was dissolved and the monks expelled. However, unlike many other religious sites, Henry spared the cathedral from destruction. Henry’s ‘mercy’ did not spare St. Cuthbert's shrine; before its destruction, the monks hid his remains in a simple tomb in the Feretory behind the high altar. During the English Civil War, Durham Cathedral became a prison for Scottish soldiers captured at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650.

More recently, the cathedral became part of local legend. It was during the Second World War and the second wave of the Blitz in 1942 when the Nazi High Command was supposedly using a German tourist guidebook published by Baedeker to target historic British cities. The British called them the Baedeker raids, and they began with an attack on Exeter on April 23 and finished with the targeting of Norwich on June 27.

Bath and Canterbury were also subject to attack, as was York on April 28, after which the BBC reported that the minster had escaped. The Lord Mayor of York complained that this was tantamount to inviting the Luftwaffe to return, so censorship of raid reporting became tighter. Therefore, we only know the barest details of the raid on the northeast of England on May 1, when 38 bombers targeted the region, hitting industrial sites in Newcastle, Sunderland, South Shields, and Jarrow. Bombs fell around Durham, too, and at the nearby Finchale Priory—which some think the Luftwaffe pilots may have mistaken for Durham Cathedral, which they had somehow lost sight of. On that fateful early morning, Councillor Fred Foster was on duty at the Durham County ARP headquarters and recorded,

"The night was clear with a full moon, and it was almost daylight. The warning of enemy bombers approaching was received at 2.33 am on May 1. When the enemy aircraft were close to the coast, a dense mist suddenly appeared over the city. It was said by someone that a smokescreen had been drawn over the cathedral and castle. It was a ground mist because the moon could still be seen clearly in the sky. Telephone inquiries elicited that the fog was not widespread. For instance, Langley Moor on one side, Chester-Le-Street to the north and Belmont to the east, had no sign of fog. It was confined to a radius of two-and-a-half miles of the city centre. The all clear was sounded at 4.02 am when, strangely enough, the fog immediately dispersed. I have since frequently heard that people in many parts of the country attributed this phenomenon to the spirit of St Cuthbert."

The medieval community sincerely believed in St. Cuthbert's miraculous abilities to control the weather. Legends tell of his using wind to extinguish a house fire and miraculously changing a gale's direction to save sailors. While a stained-glass window in the cathedral commemorates this ‘miraculous’ event, dissenting voices exist. In May 1945, a letter from George Greenwell, chief ARP warden in Durham, debunked the whole story, writing that the mist was a regular occurrence.

Anyway, that's enough history. Let's turn to the reason for my visit: to see Luxmuralis' latest offering. They are no strangers to Durham Cathedral; this was the third year they have presented their immersive art installations there.

The first, 'Life,' was in 2022, immersing visitors in a journey through earth, sea, and sky. Last year, the cathedral hosted 'Science,' which explored elements, DNA, and the most outstanding scientists in history through light, visuals, and music. Both shows proved extremely popular with thousands of visitors to the cathedral, setting lofty expectations for this year's 'Space' expectations that were more than met.

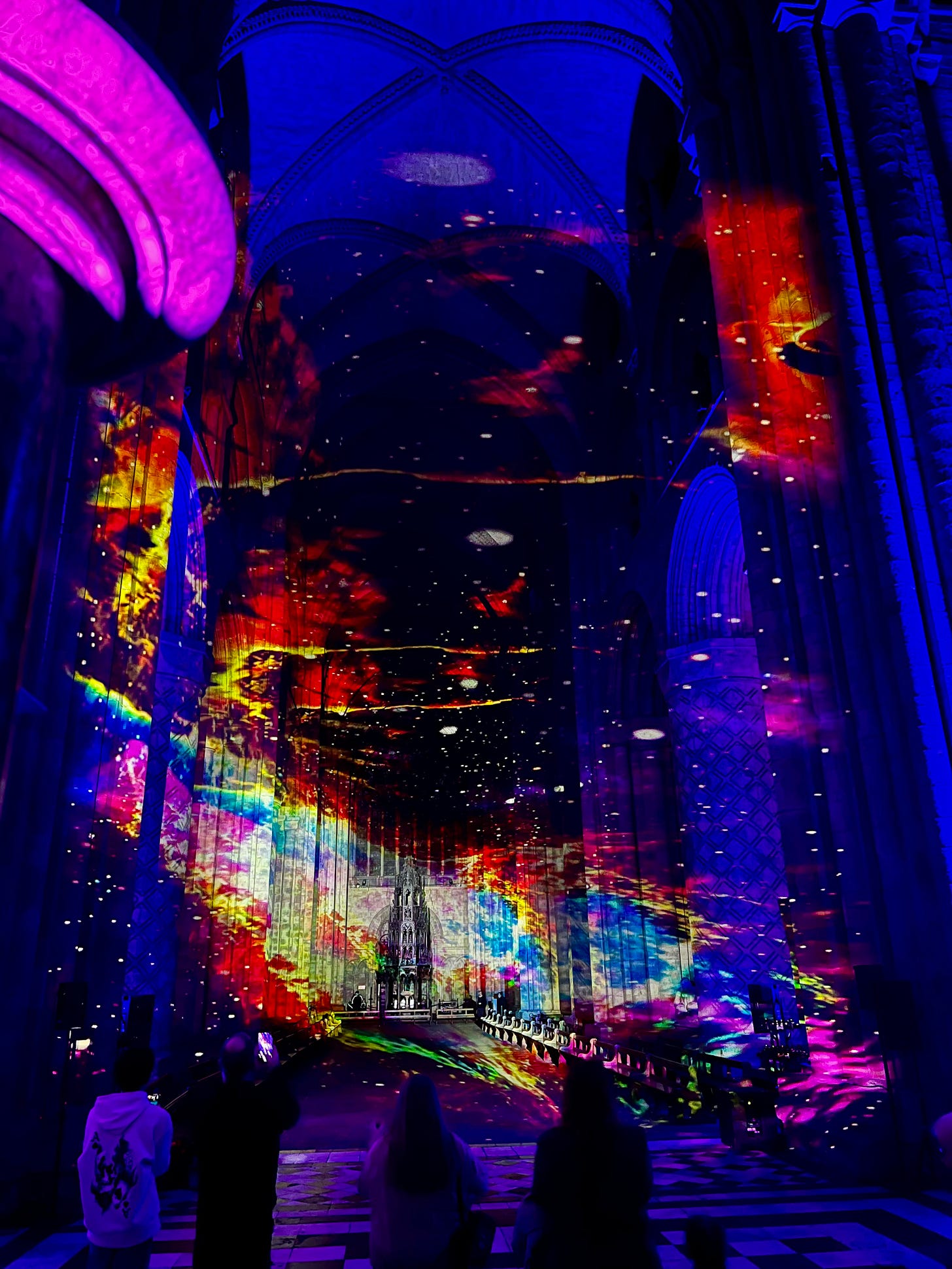

It was a very windy and wet evening when I visited, with no chance of seeing the Northern Lights that graced northeast English skies earlier this month. Therefore, with a sense of windblown relief, I entered the dry and calm cathedral in search of sanctuary from the elements. Then, my first glimpse of vibrant colours lifted my spirits at once. I imagine worshippers before the reformation might have felt the same when entering the cathedral and beholding what would at the time be a richly decorated interior rather than the bare stonework you see today. But with Luxmuralis, that stonework became a blaze of colour again as my other-worldly meander took me around the cathedral, whose walls, ceilings, floors and facades became dynamic canvases imbued with beautiful hues, images and patterns that flowed through the building, offering scenes of outer-space, galaxies, asteroids and then our own Earth.

Accompanying this series of vibrant projections was a carefully synchronised soundscape from David Harper that added emotional depth. The images and sound transformed the cathedral's interior to create an immersive experience, inviting visitors to reflect on our relationship with the universe.

The most awe-inspiring projection was in the Nave, the cathedral's substantial central aisle. The space cleared of its usual many pews, allowing visitors to take a moment to pause, looking out into 'space' and think about human achievement as a kaleidoscope of swirling pinks and blues, followed by purples and greens transformed the cathedral's soaring columns. Then echoing within that magnificent edifice came JFK's famous words about space exploration - doing such things not because they are easy "but because they are hard" - as projections featured original footage of the early USA space programme. And more magic awaited when I reached the Cloister, where projections, including references to ancient astronomer Copernicus, featured on the cathedral's outer walls, adding further splendour to the experience.

After experiencing the brilliant sights and vibrant sounds, there was a different 'space' and peace within the Galilee Chapel, where Bede’s remains lie and where those of faith could light a candle to pause and reflect. Readers will know I am not a man of faith, yet 'Space' evoked awe, contemplation and reflection in me. While the installation within the grand setting of the cathedral did not give me a feeling of spirituality, it did offer a meditative quality, encouraging my thoughts to meander on my life and the space I've occupied in the lives of others.

Oh, how beautiful is that light show! I have to tell you that Durham is my favorite cathedral in all of England. It has such a special atmosphere - partly, I think, because it is home to St. Cuthbert & the venerable Bede. I'll never forget the kind volunteer who, upon noticing that I was American, grabbed me almost as soon as I walked through the door and took me to see the Washington family shield in the cloisters, explaining that that was where the stars and stripes on the American flag came from. I just love Durham.

I am shocked to hear that Chester-le-Street is older than Durham, though! You would never guess it.