Belonging

Some photographs, artwork and some words ...

Every traveller has a home of his own, and he learns to appreciate it more from his wandering

Charles Dickens

Regular readers will know I don't take photographs in galleries, so any you see of artwork in this piece are from the 'Net'; thus, some aren't brilliant. Other photographs are mine, and they aren't too clever either!

Anyway, I visited Newcastle's Laing Art Gallery a few weeks back to see the 'Belonging' exhibition. A captivating exhibition that drew on the Laing's collection to explore what it means to ‘belong’. The exhibition included a diverse collection of artworks from renowned and emerging artists. Regional figures like Norman Cornish, Louisa Hodgson, and Charlie Rogers, as well as internationally renowned names like Paula Rego, Rineke Dijkstra, Laura Knight, and John Martin. All the pieces offered various forms of belonging, allowing visitors to delve into what it means to feel connected to people, places, and memories through geographical connections, local histories or shared cultural bonds rooted in religion, myth, and legend. The exhibition also contrasted the idea of belonging with alienation, using art to reflect feelings of nostalgia and disconnection.

The curation, led by PhD student Ella Nixon in collaboration with Northumbria University, also highlighted the pivotal role of regional galleries in promoting women's art. Delving into themes such as community and camaraderie, Ella highlighted the significant role of artistic networks—especially those among female artists in northeast England—in shaping the region's cultural landscape.

Ella offered in an interview, "Over the years, there has been a very strong network of female artists working in and around Newcastle and the Northeast as a whole. They have worked together and taught each other, and often their finished work stays within the region because it is donated or bought by friends. Likewise regional galleries such as the Laing have played a significant role in providing female artists in the Northeast a platform to showcase their work, in contrast to the national galleries which tend to collect work by so-called 'blockbuster' artists, who are typically men."

The word 'Belonging' originates in Middle English, 'belongen,' a combination of 'be-' that alone conveyed completeness or intensity, and 'longen' that referred to something due or proper. Putting those words together to form 'Belongen' meant 'to be appropriate' or 'to be suitable.' Over time, the meaning evolved to encompass the sense of something appropriate or proper to someone, leading to the concept of ownership or attachment. Thus, the etymology of 'belonging' reflects the historical notion that something 'belongs' to someone when considered proper or suitable for them, emphasising the sense of connection and ownership that comes with such appropriateness or suitability.

To me, belonging means being a part of something that you value and values you. Belonging goes beyond mere physical possession and encompasses the emotional and psychological. It signifies a sense of identity and acceptance, feeling understood, supported, and included within a particular community or context. Belonging plays a crucial role in shaping an individual's sense of self and well-being, as it satisfies the innate human need for social connection and acceptance. It can arise from personal relationships, cultural affiliations, shared experiences, or even a connection to a physical location. Belonging offers a sense of security, validation, and a foundation for personal growth, allowing individuals to express their true selves and develop a sense of purpose and identity within the context of their chosen or innate communities.

Art, as shown by the 'Belonging' exhibition, can reveal the unseen bonds that unite us all. Throughout history, art has reflected shared human experiences based on place, religion, legend, myth, and inherited traditions in natural and imagined spaces.

I love the work of Norman Cornish (I wrote of that work in my piece Norman Cornish), who chronicled through his art his experience of thirty-three years working as a 'hewer' in the coalpits in the southwest of County Durham. For the mining community, pubs provided social respite after long days spent underground, and the exhibition included Cornish's 'Interrupted Conversation' in which two pints rest on the bar, one temporarily without an owner. From the viewer's perspective, perhaps that pint is ours?

Cornish offered, "I made drawings of workers in pubs in days past because I was fascinated by the men standing at the bar drinking and talking, or sitting playing dominoes... I also realised that life would change in some ways. The local collieries have gone, together with the pit road. Many of the old streets, chapels and pubs are no more. A large number of the ordinary but fascinating people who frequent these places are gone. However, in my memory, and I hope in my drawings, they live on. I simply close my eyes, and they all spring to life.".

Cornish's words stand as a testament to the transformative power of art. Art can narrate deeply personal stories, contributing to a broader discourse, in this case, on belonging. These stories touch on personal histories, cultural connections, and the emotions of displacement or exclusion.

Local histories and landscapes play a significant role in shaping our geographical experiences of belonging. The exhibition also explored geographical belonging by juxtaposing scientific-looking maps reimagined as artistic creations, fostering a sense of connection and rootedness in the viewer.

One map I found striking was of the centre of modern Newcastle, with overlaid on it the two-mile-long wall surrounding the mediaeval town with its six gateways, nineteen towers and several smaller turrets. This defensive structure, a significant part of Newcastle's history, symbolised the town's unity and identity (the city’s motto is Fortiter Defendit Triumphans - Triumphing by Brave Defence). The first thing that sprang to mind was how small that town then was and how 'cosy' it must have felt living behind walls seven feet (over two metres) thick and up to twenty feet (over eight metres) high. it certainly impressed Henry VIII's antiquarian John Leland, who offered, "The strength and magnificence of the walling of this town far passeth all the walls of the cities of England and most of the towns of Europe." There would no doubt have been a strong feeling of belonging for the Newcastle people of the time, especially when the kilted and claymore-wielding visitors north of the border came to pay one of their regular 'visits.'

Another piece I particularly liked is Thomas Miles Richardson's watercolour, 'View of the Ruins of Tynemouth Monastery.'

The priory's dramatic cliff-top position has always attracted artists. This popularity underscores the significant role of architecture in creating a shared sense of place. In Richardson's painting, the powerful beams of light streaming through the arches amidst stormy clouds and choppy waters speak of nature's imposing power.

Another work, Ralph Hedley's 'Sketch for Seeking Sanctuary,' in which a vague figure clutches the ring of the door 'knocker' of the north door of Durham Cathedral, reminded me of the story my father told me on a visit to the cathedral when I was a small boy.

I wrote about the cathedral's history in my piece last week. However, I did not mention what looks like an impressive knocker called the Durham Sanctuary Ring. The ring is a snake held in a lion's mouth (what you see in my photograph below is a replica of the 12th-century original, which now resides safely in the cathedral). Once upon a time, a monk sat on watch in a small room with a window above the door, and as soon as he saw someone grasp the ring, he would ring a bell to declare the granting of sanctuary. Those who "had committed a great offence" then had thirty-seven days of sanctuary within the cathedral, during which they could try to reconcile with their enemies or plan their escape. An early 17th-century act of parliament stopped the principles of sanctuary.

Interestingly, the replica includes what looks like a bullet hole in the lion's skull. My father's story was that a person seeking sanctuary grasped the ring just as one of his pursuers fired his pistol. St. Cuthbert's divine intervention then diverted the ball from striking the escapee and striking the lion's head instead. It's a delightful story, as are the other stories that offer a cause. It was an arrow, not a pistol ball; it was a bored, passing 18th-century dandy who fired off a potshot for fun. In truth, no one knows.

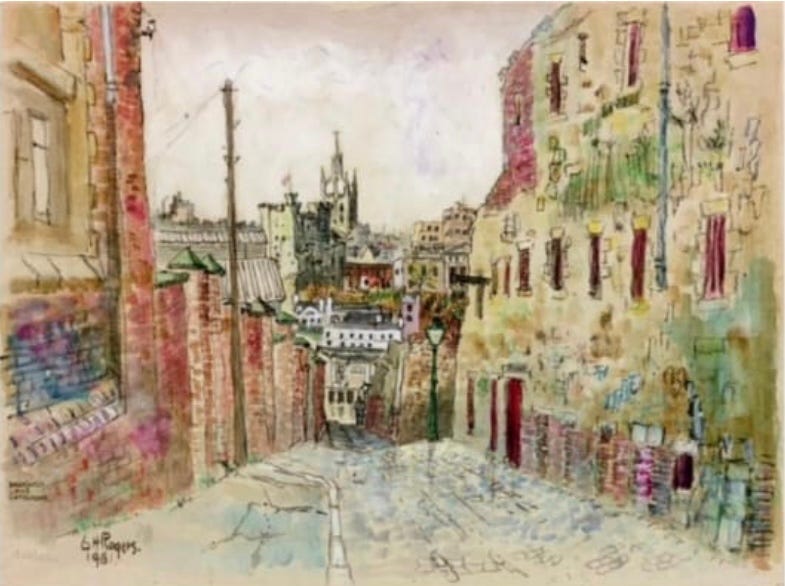

Self-taught Gateshead artist Charlie Rogers 'Bankwell Lane Gateshead' looks idyllic with its vibrant colours and higgledy-piggledy charm. Yet this nostalgic view belies that it was a notorious slum-like area of Gateshead. Although demolished by the mid-1970s as part of broader redevelopment, such places fostered a keen sense of belonging and identity despite the hardships endured by the people who lived within them.

When it comes to belonging to a faith, a good example was John Martin's etching, 'Creation of Light'; God is visible in the centre of the piece at the beginning of the world's creation with the conjuring of light from nothingness in a fantastical religious composition typical of the Northumberland-born artist John Martin. This piece and his 'The Covenant' also in the exhibition were illustrations to an 1825 edition of 'Paradise Lost' by the poet John Milton, as were other high-quality mezzotint prints by Martin.

While such pieces could offer a nostalgic belonging, the exhibition also included pieces on separation and alienation, with many artists creatively exploring this negative experience— of a bygone or imagined era or the capture of stilted body language and discomfiture.

The neo-classical 19th-century architect John Dobson was the most noted in Northern England and best known for designing Newcastle's Central Station, fifty churches, and a hundred private houses. In Victorian Britain, graveyards functioned as sacred spaces for visitors to reflect upon death, hoping to one day meet their loved ones again. This etching by Dobson depicts Jesmond Cemetery and the archway, chapel, and gates he designed; aptly, he ultimately was laid to rest there, too.

Louisa Hodgson's 'Mother and Child Study for Nativity' depicts an uncompleted figure in crumpled bed sheets, with folds meticulously captured, resulting in a composition where the figure appears less significant. The finished painting 'The Nativity' caused controversy when displayed at the Royal Academy due to its modernist reimagination of the traditional biblical story, with a Bethlehem stable replaced with a modern hospital ward. Alas, the belief is that bombing destroyed the completed painting during the Second World War.

Hodges, known mainly for her tempera paintings, gained a reputation at the Royal Academy in the 1930s and 1940s for her 'problem' pictures, which refer to her modernist reworkings of traditional subjects. This alienation despite the acclaim she achieved in other quarters. Sadly, Hodgson spent her final years privately, leaving little information about her life and career.

Photography also played a crucial role in the exhibition. The Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra is interested in how several figures relate when captured in a singular photograph. Rineke's capture of everyday moments in various communities aims to show how belonging is experienced or, in some cases, longed for in an honest but quiet beauty as seen in her 'Vicki, Lynsey and Adele, Ponteland High School, Newcastle, 18 February 2000'. This photograph captures three adolescent girls. It's monumental, placing the viewer face-to-face with the problematic transition period that can fuel feelings of alienation. The girls' uniforms may suggest conformity, but their postures and expressions show otherwise.

Ella's curatorial decisions at Laing Gallery are deserving of praise. The exhibition's strength lay in its ability to balance personal narratives with universal themes, creating a relatable journey for the visitor and making them feel included in a larger narrative of belonging. Her guidance through the different themes of the exhibition was informative without being didactic. The layout flowed seamlessly, creating a dialogue between works. The careful grouping of pieces encouraged reflection but left room for individual interpretation. The transitions between the sections—each exploring a different side of belonging—felt natural, fostering a contemplative and immersive experience. This approach respected the audience's intelligence and invited them to actively engage with the artworks and the exhibition's themes.

For me, 'Belonging’ was not just an exhibition of visual art but an exploration through which we can discover ourselves in both positive and negative guises, and in discovering ourselves, we can find our way 'home'. 'Belonging' asked questions about our connection to others and places, making it a highly relevant exhibition in today's context of cultural displacement, migration, and changing identities. The blend of media, the quality of the works, and the thoughtful curation made for an influential exhibition.

And where do I belong? It was only after Sarah and I became a LAT couple two years ago and I moved back to northeast England that I realised I belonged here. I left as an 'economic migrant' over fifty years ago to live and work in London, and I don’t regret it for a minute. I enjoyed the decades I lived in the south of England, for which I have much to thank. The opportunity to build a successful career there and to find love there, my children were born in southern England (though the eldest son supports NUFC - and I applied no pressure - guess like his dad, he prefers hope to expectation). I made my oldest friendships there, and we geriatrics will meet again in December for a beer or two in the good old Chandos in London. Despite its location so close to Trafalgar Square, just behind the statue of the brave Edith Cavell, it serves northern beer at a reasonable price (albeit not an actual northern price). And when it comes to London, I fell in love with the place at first sight on 6 July 1974. That love has lasted and will last the rest of my life, and I regularly return to get my 'fix' of noise, dirt, jostle, hustle, and bustle. I also have very fond and warm memories of the southwest of England and the friends I made there. The region reminded me a little of the Northeast somehow, but the Northeast makes me feel I’m home.

When living in the south, I told people I was from northeast England. I know now I should have said I am of the northeast. I returned regularly during my decades living in England's south. To see my parents when they were still around and to watch NUFC lose. Those who are regular readers will know of my pride when, in the 1990s, the company of which I was a director opened an A&D systems development office in Newcastle that was part of my responsibilities and meant frequent visits. Yet none of those visits to parents, football or business were long enough for me to thoroughly understand my affiliation with the region. It took my return to live here to realise I am one of its people and share the DNA of their work ethic, cultural outlook, biting humour, dogged determination, welcome of strangers of all colours and creeds and independence of mind and innovation. And language! I love the hinnys, kiddas, marras, why ayes, hadaways and that Swiss Army knife of northeast words, canny! And I never have the problem in the Northeast that I have in the South when I order a Coke in the pub and receive a quizzical look followed by, “Why do you want a cork? “

The people of the northeast of England offer a warm embrace (maybe the weather not so much, but in some perverse way, that too is an attraction - although I'd draw the line at using that word for the scything east wind that can sometimes blow off the North Sea). I love that when I walk down the street, people I pass offer a smile and a hello, hi or alreet? And it's not just those of my age; those of younger years seem to fall into the habit without prompting, although maybe I get more head nods from those of teenage years rather than words. It is as if no one is truly a stranger in northeast England but more someone deserving of acknowledgement and made to feel they belong. And, at heart, isn't that what brings the most happiness in life? The feeling we belong. Be it in a place, with a person, part of a community, within a faith or with your mates.

Wonderful article today,Harry, nice break from Politics 🤗 and will reStack ASAP 💯👍

Nice piece, which made me realize that to belong doesn't just mean to feel a connection to a place or community (like I did until now), but also -- just as important, to feel that those people also value you back. And I liked how you connected this theme with art too. After all, we learn our biggest lessons from art, I believe.